The work of director and teacher Nelda Castillo represents one of the most solid and coherent poetics in the contemporary Cuban scene. Her research, conducted through the dynamics of group theater, has enabled her to explore the deep links between memory and national being amid the rigors of contemporary Cuba. Texts that have been set aside or forbidden or that are simply not well-known have allowed her to present onstage a dialogue with the country’s cultural and civil history. Her shows, performances, and interventions are the result of a peculiar strategy of language, entailing a convergence of a distinctive ethical posture on theater and on the participation of the artist in society and a stark analysis of the island’s transformation and present, all undertaken through a rigorous examination of contemporary scenic languages and particularly the work of the actor.

An actress by training, Nelda Castillo was a founder of the Buendía Theater, a collective created in the classrooms of the Instituto Superior de Arte during the second half of the 1980s by the actress and director Flora Lauten (Cárdenas, 1953). In this group, Nelda Castillo worked as an actress and an assistant director in renowned shows like Virgilio Piñera’s Electra Garrigó (1984), Rolando Ferrer’s Lila la mariposa (1985), and Raquel Carrió’s Las perlas de tu boca (1988). For the latter piece she created a popular, chatty character called El Chivo that would influence her career and her research path.

As a member of the Buendía Theater, Nelda Castillo directed her first shows, three of which were conceived as children’s theater—Salvador Lemis’ Galápago (1985), Monigote en la arena (1987), and Un elefante ocupa mucho espacio (1989), which was inspired by narrations by the Argentinean writer Laura Deveatch. These works were followed by Las ruinas circulares (1992), a peculiar scenic reading of Don Quixote, inspired by texts by Miguel de Unamuno, José Martí, and Jorge Luis Borges. Starting with Un elefante ocupa mucho espacio—a play that the director would return again—as well as Las ruinas circulares, we can begin to speak of the development of a distinctive poetics that Castillo later took up in her own artistic collective.

Founded in 1996 with three of her students in the Instituto Superior de Arte, El Ciervo Encantado [The Enchanted Deer] has constituted one of the most creative and unsettling forces in the Cuban scenic landscape from the first half of the 1990s up to the present. While heading this group, Castillo premiered El ciervo encantado (1996), De donde son los cantantes (1999), Pájaros de la playa (2001), Visiones de la cubanosofía (2005), Variedades Galiano (2010), Cubalandia (2011), Rapsodia para el mulo (2012), and Triunfadela.[1] Apart from this work, the group has put on three small pieces that have formed part of the three productions of Café Teatro—La Siempreviva I (1998), La Siemprevivia II (2004), and La última cena (2013)—as well as other performances and public interventions that, in breaking with the traditional dynamics of the production and presentation of theatrical shows, have afforded the group an idiosyncratic profile within the cultural field of Cuba and the Caribbean.

I

Participating in a Caribbean tradition irrigated by diverse cultural sources, El Ciervo Encantado’s oeuvre has peculiar links to a creative line of work that the Cuban essayist Nancy Morejón has called the “poetic of the altars” (1994).  This poetics goes beyond a thematic coincidence, transcending the mere presence of ritual elements or of religious characters and participants. In Nelda Castillo’s theater, the show itself becomes an altar. Her distinctive creative strategy and selection of sources, including texts, images, and soundtracks; the condition of the actor as officiant/performer/ medium (an intermediary between those participating in the work and the spectators); the process of preparing a performance, including research, psychophysical training, and convocation; and the performance’s function as a ritual of memorialization, exorcism, and conjuring all connote the scenic poetics of this collective.

This poetics goes beyond a thematic coincidence, transcending the mere presence of ritual elements or of religious characters and participants. In Nelda Castillo’s theater, the show itself becomes an altar. Her distinctive creative strategy and selection of sources, including texts, images, and soundtracks; the condition of the actor as officiant/performer/ medium (an intermediary between those participating in the work and the spectators); the process of preparing a performance, including research, psychophysical training, and convocation; and the performance’s function as a ritual of memorialization, exorcism, and conjuring all connote the scenic poetics of this collective.

In her essay, Morejón defines the “poetics of the altars” based on the meaning established by Fernando Ortiz in his Nuevo catauro de cubanismos. Ortiz states that an altar is a “combination of illusions or things disposed to a particular end.” Further on, the poet and essayist adds: “our altars are in themselves a proposal to organize—as artistic expression—the elements that conform nature, namely: water, air, fire, earth” (1974, 66). Elements and illusions shape a plural assemblage, full of multiple signifiers that function as mirrors before which each person finds meaning on the basis of her own referents. In this same line of argumentation, the researcher José Millet, in his Glosario mágico religioso cubano reminds us that the altar is:

Sanctuary, tabernacle, table, or shelf on which diverse objects are placed with a ritual function. Sacrifices are realized around it—sometimes bloody, sometimes bloodless—to the pertaining deities or genies. Magic-religious ceremonies are also executed on or around it—sometimes simple, sometimes complicated ones—such as greetings, vigils for saints, prayers, meals, supplications, divinations, consultations, etc. (1994, 7).

He specifies that “there are as many altars as there are members of each diverse religion.” It is this multiplicity that leads him to assert that each altar expresses “a personal vision of the world that, anchored in a more general conception, symbolically particularizes the essences of the being that organizes it and its circumstances, while leaving open the possibility of being reorganized by the devout and sensible experience of other people that approach it, recognizing its nature as a living creation” (Gómez Triana 2012, 33).

The altar is, then, an open and always collective creation that, as it roots a specific identity that is decanted with time, never stops receiving new contributions that actualize, refocus, and amplify it. Its rhyzomatic quality and its multiplicity are its best strategy of communicating with others who, even if they ignore the principal signs of religiosity and faith that are deposited in it, can verify its cohesion, its force, and its capacity to express and reflect desires and fears. Beginning with this framework, we can undertake a tour through the work of Nelda Castillo, considering in each piece the elements that form this “poetics of the altars” and emphasizing not only the elements of this aesthetic in the group’s productions, but also the communication strategies and efforts to shape audience reception that they employ inside and outside the theater, as well as in the liminal space between inside and outside.

In the first place, we might refer to the training that leads the actor through a “negative path,” as postulated by Polish director Jerzy Grotowoski (2002, 17). To unlearn standardized behavior and eliminate tensions through breathing and sighing; to channel the forces of the pelvis as the main energy core in which action originates; to amplify the sound and the total projection of the body; and to break open the blockages that obstruct self-expression are some of the objectives of this training as developed by Nelda Castillo. Their function is to empower a body-channel and enable it to be inhabited by beings that are largely autonomous and always enigmatic, embodied amid every process-ritual.

Without a doubt, the research work that paves the way for the creation of every show has an important value for this group, as well. Theirs is a research process that goes well beyond the study of sources and the selection of a particular scenic language. For the director it is indispensible above all to discover the subject that urgently needs to be broached, a theme that connects the members of the group in an essential way with their context and, once this primary link is established, with the audience. Free from automatisms, obstructions, resistances, and apprehensions, the body-mind selects, fixes, and amplifies that which is essential. Archetypal behaviors then are free to blossom, behaviors that are in collective memory and are a testimony to the biological and cultural evolution of the human species.

It is precisely because of this approach to content that the actor constitutes the focal point of Nelda Castillo’s creative process. Nevertheless, the “actor” does not refer to specific persons with distinct skills, but rather to that peculiar state that resembles not Grotowski’s holy actor, but the caballo [horse] of santería. On the basis of this training, the actor/performer distills and unveils inner truths with ever-deepening layers, as well as general and specific variants pertaining to each show or proposal. These truths allow the actor to erect an individual altar that is confronted with others and submitted to the peculiar synthesis of the director—who is also an actor and the main researcher—based on each actor’s own organic experience and specialized training.

II

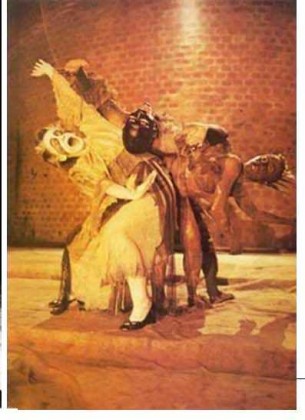

The historical and psychosocial memory of Cubans and the historical process of the island represent the main themes the collective has approached since its establishment. El ciervo encantado—the show that gave the group its name, based on a tale written by the Cuban patriot Esteban Borrero Echavarría and in dialogue with Virgilio Piñera’s “La isla en peso”—staged a singular allegory that synthesized the past, present, and future of Cuba. 18 years after its premiere, we can still find relevance in this past-future. The identification of a deer with freedom and the permanent hunt for the elusive animal that Cubans have engaged in represent not only in the main key to decode the show, but also the keystone of all the research undertaken by the group since then. Texts by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, José Martí, and Fernando Ortiz, together with the music of the Valera-Miranda family, descendants of the mambises [patriots of the Cuban independence wars], compiled in the album Antología general del son (Vol. 1), are some of the sources of this mise-en- scène. The work presents three beings materializing from the afterlife: the indian María Belén Chacón, the creole Dolores de Gloria, and the free black Nengón, who mix the shades of their skins (the characters are performed with masks of makeup, and paint covers their whole body), enacting a new scenic allegory, in this case about the process of transculturation.

These beings’ condition as ancestors/archetypes, the ritual value of their actions and their words, and the quality of the scenic space, which takes the form of a black backdrop disrupted only by the presence of a small altar perched to a side of the stage and a banner in the proscenium bearing the phrase “TO ETERNAL MEMORY,” display a ritual sense that are a constant in other works. The banner acts in the staging as a double reference to one displayed in the shield of Villa de San Juan de los Remedios and another carried by two angels in the holy card of the patron saint of Cuba, the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre [Our Lady of Charity]. In the shield there is an image of an island with three palms, and in the holy card there is a representation of three figures that popular tradition has denominated the three Juanes of the virgin: Juan Indio, Juan Blanco, and Juan Esclavo [Juan Indian, Juan White, and Juan Slave]. The selection of different symbols fused together within a work that attains its own autonomy and therefore becomes a greater allegory of the history and present of the island is a constant characteristic that reappears again and again in El Ciervo Encantado’s shows.[2] The staging, however, does not merely represent an icon, but rather activates a profound multidirectional communication that works substantively in its context.

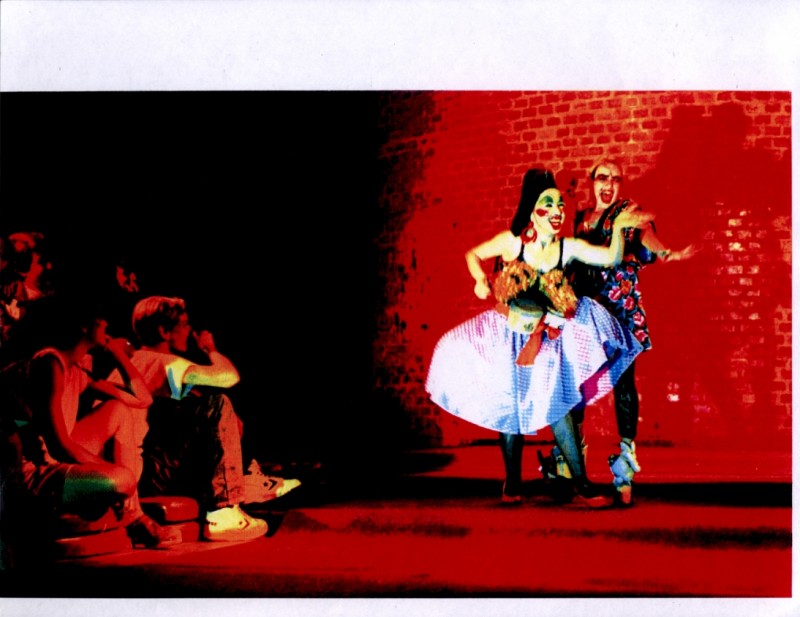

De donde son los cantantes, which premiered in 1999, is based on the 1967 novel of the same name by Severo Sarduy and fulfills through theatrical artifice the writer’s wish to be buried in his native Camagüey beside the tomb of Dolores Rondón. The iconography and music of Tropicana, the most famous Cuban cabaret of all time, contribute a fundamental element to the visual dimension of the play. Sarduy’s Siamese twins, the inseparables Auxilio and Socorro, are the masked characters who mutate repeatedly in front of the audience. The announcer of Tres tristed tigres, Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s novel, provides the key to penetrate the theatrical universe that prompts this game of transformations.

Nocturnal Havana is also convoked here. Its reconstruction seeks to summon the writer, to compel his journey from east to west, his return trip to the island. The announcer opens the space game and invokes the gentleman of Paris, who is no longer the picturesque Havana nomad, but Severo, who, transformed into a lotus flower and the errant Christ of the procession, will finally appear to answer the audience’s questions. Auxilio, Socorro, and Severo, through their successive metamorphoses, are the fundamental triad. The staging as a propitiating ritual ends up rendering the deceased writer present. Dolores Rondón also appears, transforming the cabaret into a cemetery. Stage and tomb are here different avatars for the same altar, which is constructed and deconstructed before our eyes. The act completes what the writer had prophesized in one his epitaph-poems: “I will return, but not in this life / I say everything is flayed / and the cold the lime afflicted / in the bones. How daring / the skeleton that invites / to dance in its own way! / I cannot contradict her / Life is a strong dream / From one death to another / and I prepare to awake” (Sarduy 1999, 251). To return to life is also to return to Cuba.

Another one of Sarduy’s novels served as the main source for the show Pájaros de la playa. Taking its name from the writer’s posthumous piece, the show approaches the arid and corrosive landscape of illness. Instead of resorting to the main characters of the fable, though, the staging focuses on the anonymous sick people it portrays. AIDS, which was the cause the Cuban writer’s death, is seen here as a metaphor for other ailments of the spirit that can also end up annihilating life. Centered on the imponderables of existence, the show acts as an exorcism through which the actors invoke not specific beings, but rather, taking into account their own ailments, construct new, mutating archetypes that confront us with the realm of the terrible by way of overlapping monologues. The illness speaks of the individual, of the human being, but in their convergence the actors embody a collective, social being that, in denouncing “the horrors of the moral world,” propose a new metaphor of the peculiar circumstances of the island.

To access the stage piece, one must traverse a space that is at the same time changing room and sickroom. Objects accumulate in that space, each of them bearing a high sentimental value for some of the actors. Once again, the audience finds itself before a triad, sustained in this case only by the materiality of three nylon cloths. The images evoke the paintings of El Greco and the engravings of Francisco Goya, as well as the paintings of Fidelio Ponce and Antonio Eiriz. Decay, sickness, apathy, and pain are superimposed, and the deceased surrender to a holocaust. Body and memory are presented together as an offering of hope for a miracle. With eyes nailed to the horizon, the ghostly figures undulate waywardly in a storm, invoking a hunt-like act that we have already noted in El ciervo encantado. Reinaldo Arenas’ poem “Introducción al símbolo de la fe” offers the final clue. It is from this text that the last words of the show are taken: “we continue to seek you, poem, we continue to seek you, earth, we continue to seek you, happiness” (Castillo 2012, 109).

In Visiones de la cubanosofía the condition of the altar-spectacle becomes even more evident. Inspired by the article of Cuban psychologist Alfonso Bernal del Riesgo entitled “La cubanosofía, fundamento de la educación cívica nacional,” the show resumes the analysis of Cubanness, in this case from a historical perspective. The vision of the island’s historical process is inspired by Reinaldo Arenas’ diachronic proposal in his poetic trilogy Leprosorio. A group of archetypal characters appear one after another under the tutelary mantle of the patron saint of Cuba, Our Lady of Charity, and before the eyes of José Martí, who is considered by many to be the greatest of all Cubans.

A three-level scaffolding supports the image of national identity as a work in permanent construction. It is populated by an assortment of characters both archetypical and distinctive. The bearded queen on high, symbolic of the power that imposes slavery; the mutilated and defeated mulata displaying herself as haughty and victorious; the traveler who arrives from faraway lands, admiring of and befuddled by the behavior of the natives and recognizing the exotic character of the landscape; the crazed and paranoid improviser; the scientist absorbed in complex reflections and attending to the most pedestrian of daily needs; the intellectual, the only one who is able to escape the oppressing context through his work; and the city itself, personified, trying to repair its streets and bearing a tough testimony on distancing and uprooting. The show tries to answer a simple question: what happened to us? As in El ciervo encantado, this is a staging of history on the basis of immersion in the psychophysical memory of the actor. In order to carry this history out, the work presents a dialogue of different icons, and the altar-artwork returns to the idea of the storm. Under the virgin’s mantle, the three actors become again the three Juanes saved in Nipe, transformed into alter egos of all Cubans.

With 2010’s Variedades Galiano the group and its director entered a new phase in their work. Moving beyond exploring the memory of national being and the synchronic confluence of the historical process in the national imagination, Nelda Castillo becomes interested in delving deeply into the island’s present, with an emphasis on the profound crisis of values that resulted from the economic collapse of the 1990s. Among the literary sources of the stage work are the poet Reina María Rodríguez’s book Variedades de Galiano and a compilation of the poems of Flor Loynaz. Beyond that, the members of the group went out to gather the pulse of the streets, taking recordings and appropriating the sounds of urban hip-hop.

The reopening in 2008 of one of the main shopping centers in the Centro Habana neighborhood, once named F. W. Woolworth Company’s Ten Cents and transformed now into the TRASVAL hardware store, contributed the main focus of this work. Rechristened in the 1970s as Variedades Galiano, the well-known store, whose front windows were symbolic of the scarcity of resources during the 1990s, opened its doors in 2008 transformed into an opulent establishment selling goods at prices that were prohibitive for most Cubans. The acronym identifying the rejuvenated store stood in literally for “value transfer.” The appearance and content of the new store generated a stark temporal contrast in social and urban terms, constituting an indelible sign of the new times.

Three characters—devastated, excluded, and dispensable—serve as the protagonists of this new work, which presented itself as a live action, onstage performance of survival. The feelings and representations of weariness, violence, and senselessness were perhaps the main active elements of this piece. They are embodied by the three principle characters: the Queen, a disabled woman inspired in the image of Flor Loynaz, Simon, a.k.a. La Claria, a marginal character who learned on the street the credo “every man for himself,” and El Mulo, a being without consciousness, who carries the last fragments of a decayed altar and makes his maraca rattle in a gesture of final hope. The work reflects the most painful side of the island in a real urine puddle, making an urgent plea for the recuperation of civil consciousness and for not leaving in the hands of others the solutions to the nation’s most urgent problems (Gómez Triana 2012, 41).

III

A deep reading of these works reveals the characters of Variedades Galiano as equivalent to those in the group’s first piece. They represent all Cubans; they are the Juanes of Our Lady of Charity, the mutant trinity that returns to us via the stage a peculiar experience of Cuba. Each piece, however, functions as an organic, living installation that claims its own autonomy while constituting an artistic materialization of a particular strategy for thinking about national being on the basis of the identity of the creators. The notion of the altar appears here to sustain a permanent exercise of construction/deconstruction of icons, stereotypes, and behavior rooted in the idea of the perpetual unfolding of the Cuban nation—a concept that, with its many variants, continues to feed the conceptual basis of the more recent work of the group, such as Cubalandia, Rapsodia para el mulo and Triunfadela, at the same time as it resonates with the myriad performances and public interventions that the group has carried out since 1998.

Works Cited

Castillo, Nelda. 2012. El Ciervo Encantado: Textos de la Memoria. Havana: Letras Cubanas.

Gómez Triana, Jaime. 2012. “Hacia un teatro soñado. Coordenadas para atrapar al Ciervo Encantado,” en El Ciervo Encantado. Textos de la Memoria, editado por Nelda Castillo. Havana: Letras Cubanas.

Grotowski, Jerzy. 2002. Towards a Poor Theatre, edited by Eugenio Barba. New York: Routledge.

Millet, José. 1994. Glosario mágico religioso cubano. Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente.

Morrejón, Nancy. 1994. “Poética de los altares,” Conjunto 99 (Oct-Dec): 65-69.

Ortiz, Fernando. 1974. Nuevo catauro de cubanismos. Editado por Angel Luis Fernández Guerra y Gladys Alonso. Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

Sarduy, Severo. 1999. Obra completa. Edición Crítica. Tomo I. Madrid: ALLCA XX.

Notes

[1] For more information about El Ciervo Encantado’s shows, see the group’s website: https://elciervoencantado.blogspot.com. It is also possible to consult the websites of each show and of the group itself in the Cuban Theater Digital Archive: https://www.cubantheater.org.

[2] The 1996 show was followed by a new version of Un elefante ocupa mucho espacio, a piece that the director considers important for the general training of her actors, not only because of the skills that it demands, but also because of the conceptual proposal of the work. Laura Deveatch’s fable for children presents a frightened elephant who is afraid of disappearing. The staging constructs the animal through colorful beach balls; his image appears and disappears before the eyes of the audience. All the actors are responsible for this metamorphosis. For the director, the elephant does not exist without everyone’s participation: their collective identity transforms him into a circus soul. As in El ciervo encantado, the three beings constitute an ethno-sociological image of Cuban national being. In Un elefante ocupa mucho espacio the actors—jugglers, magician, clowns, and ballerinas—embody an artifice that becomes an allegory of theater itself.