In 2012, to celebrate the 15 years of El Ciervo Encantado, Jesús Ruis, together with Nelda Castillo and Mariela Brito, organized a retrospective exhibit on the group’s oeuvre in the Raúl Oliva gallery titled A la eterna memoria (To Eternal Memory). The exhibition opened with a performance in the group’s headquarters

To Eternal Memory

22 February, 2012

El Vedado, Havana, Cuba

It began with a procession down Línea Street of their Virgin statue from Visions. They moved as if in a conga line until they reached the gallery.

Performative Roundtable

20 March, 2012

Raúl Oliva Gallery. Bertolt Brecht Cultural Center, Havana, Cuba

Mariela Brito, Sahily Tamayo, Jaime Gómez Triana, Vivian Martínez Tabares, Norge Espinosa Mendoza

A month later, another performance took place:

A month later, another performance took place:

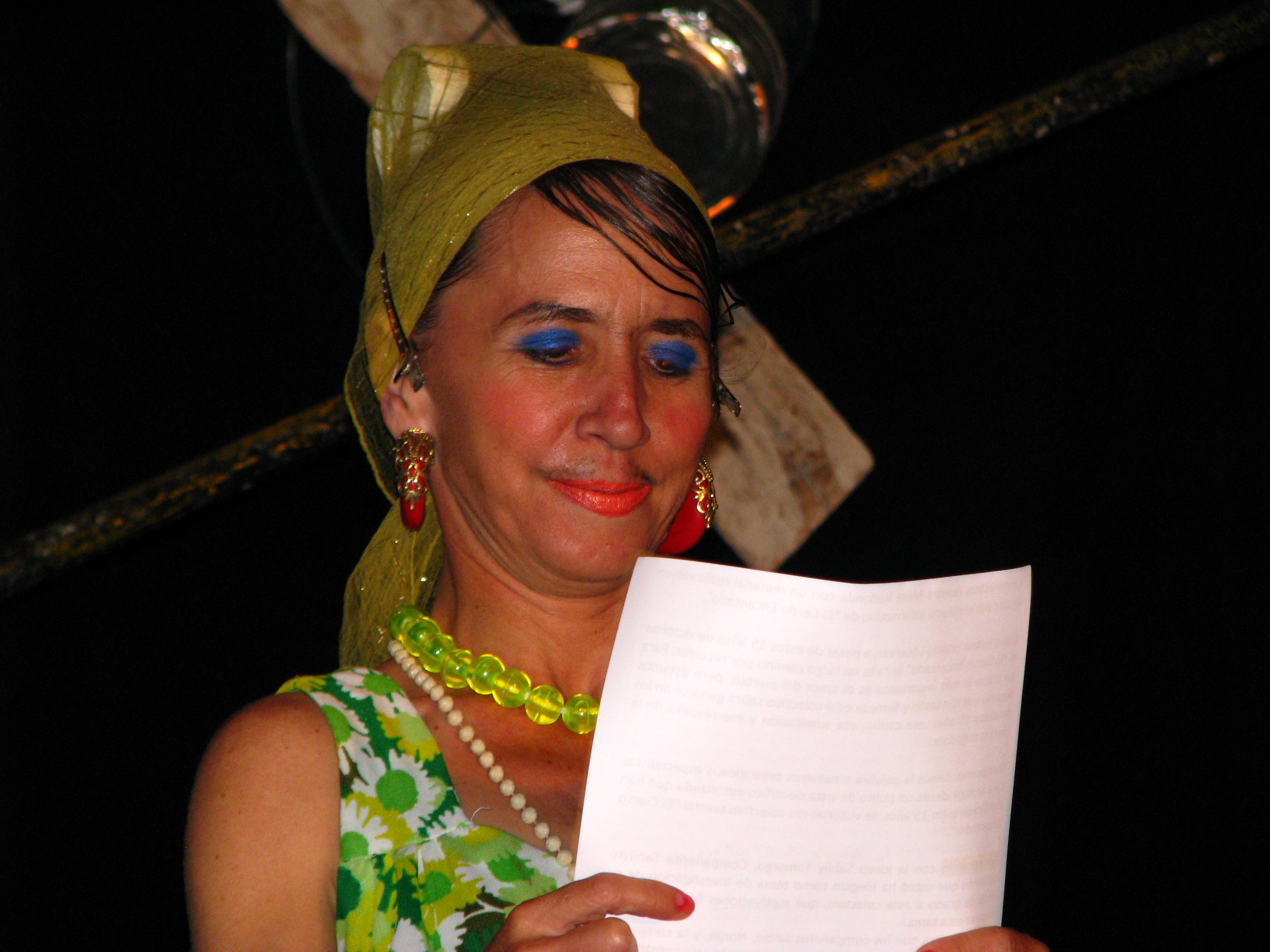

Mesa redonda performativa (Performative Round Table), in which critics talked about the group’s work. The performance and the language used by comrade Chela/Marcela Brito to recount El Ciervo Encantado’s “15 years of victories” parodied the well known Cuban television show La mesa redonda (The Round Table).[1] The performance ended with a gesture of gratitude and solidarity when Chela handed each critic a potato—a product that had “disappeared” at the time from the marketplaces. Once more, El Ciervo shared a wink of complicity with its audience: honorable comrades like Chela, as well as artists, had no choice but to participate in the informal economy or black market, both operating on the basis of the convertible currency (CUC). The parody of this parody of “The Round Table” unfolded in the last Café-theater of The Last Supper, in which the actors of the group embodied the critics to reveal the way in which each one’s characteristic language is governed not just by generational differences but by the institutions they “represent.”

In the booklet of the exhibit titled “A la eterna memoria,” Gómez Triana writes:

Work in progress, store, warehouse, chapel, silo, spare room, temple, changing room, house, washroom, carpentry, enigma, barracks, stands, library, labyrinth, cabaret, theater, basement, sacristy, fambá[2] room, confessional, statelet within the island, altar, field after the battle, museum of eternal memory, phalanstery, temporal facility, tomb, mirror. This show is all of that and more. Do not be fooled, you are not dealing with a chaotic accumulation of antiquated objects. Everything is alive, everything vibrates, everything moves, everything speaks. There are no answers, only an accumulation of questions here: Where are the singers from? (2012)

These words underline, on the one hand, the “poetics of the altars” through which the critic had read the group’s performances. But we can only find the answer to the question that has guided the performances and the investigation of El Ciervo Encantado (where are the singers from?) in the poetics of the mangrove. In the words of Nelda Castillo, El Ciervo Encantado’s performances question “Cubanness” “from the standpoint of commitment, but also of devastation, of hurt from the things that we criticize” (Provenzano and Bokser 2010, 14). Nonetheless, as we have seen, “Cubanness” turns out to be a palimpsest written on the bodies of those who stayed in Cuba, through whom one can “read” or remember the history and the memory of the bodies and the texts of those who left. But in the bodies of those who stayed behind, one can also “read” the repertoire of many others who immigrated to the island centuries before or were taken there by force and who now constitute Cubanness. In this ongoing investigation, first of the past and then of the present in order to imagine the future (remember Vásquez’s “the old” and “the future”), Cubanness in the performances studied cannot be understood as an essence, but rather as an identity in the process of becoming, rhyzomatic as a mangrove inasmuch as every answer points to another question.

The retrospective itself might be read as a sort of palimpsest/mangrove, in which one can observe the impulse of inscribing the past of Máximo Gómez’s Battlefield Diary. The audience and, above all, all of us who are assiduous followers of El Ciervo Encantado, experienced each space of the exhibit as a recreation of the different stages of this group and of the insular and international spaces in which El Ciervo has intervened and which it has transformed. There is no doubt that for this group and for the unwritten history of Cuban theater and performance after 1989, as for Máximo Gómez, “it is better to let the facts speak for themselves” (1941).

[1] The program began in December 1999 amid the campaign for the return of Elián González to Cuba. It is and was the center of “The Battle of Ideas,” a series of actions and programs coordinated by Cuban cultural institutions, which seek to take the culture to the masses and to transform cultural spaces into political and social ones (“Programas”).

[2] A semi-secret room for sacred altars and offerings.