Café-Theater La Siempreviva

2004

Instituto Superior del Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba

Café-Theater La Siempreviva began in 1998 with the objective of advancing an artistic and creative dialogue with the Visual Arts Department of the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), in whose conference room the group had settled the previous year. The abandoned space had become a junkyard, and the labor of cleaning and conditioning the space gave the group visibility. Although the collective had originated in the classrooms of the then-called Performing Arts Department of the ISA, the displacement to the Visual Arts Department, after a brief nomadic period through several spaces in Havana, would mark a new direction in the creative strategy of the group, especially regarding its dialogue with different types of artists. They refashioned that junkyard into a theater, where they worked until they were expelled; from it, El Ciervo Encantado created a series of café-theaters that overflowed the boundaries of theater as a genre. In this space with porous borders, beings that were born in theater pieces presented themselves independently as beings/performers who shared their story in the audience’s here-and-now.[1]

Café-Theater La Siempreviva began in 1998 with the objective of advancing an artistic and creative dialogue with the Visual Arts Department of the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), in whose conference room the group had settled the previous year. The abandoned space had become a junkyard, and the labor of cleaning and conditioning the space gave the group visibility. Although the collective had originated in the classrooms of the then-called Performing Arts Department of the ISA, the displacement to the Visual Arts Department, after a brief nomadic period through several spaces in Havana, would mark a new direction in the creative strategy of the group, especially regarding its dialogue with different types of artists. They refashioned that junkyard into a theater, where they worked until they were expelled; from it, El Ciervo Encantado created a series of café-theaters that overflowed the boundaries of theater as a genre. In this space with porous borders, beings that were born in theater pieces presented themselves independently as beings/performers who shared their story in the audience’s here-and-now.[1]

They performed, accompanied by the improvisations of young musical artists, visual artists, and theater artists, who have always been loyal followers of Nelda Castillo. The need to contribute a space for professional-level artistic interaction in the Instituto Superior de Arte—an interaction that had nearly disappeared during the economic and social crisis of the 1990s—largely motivated the conception of the café-theaters. The performances that took place in this new space were called Café-teatro La Siempreviva. Continuing with the effort to recover cultural memory, those involved took the name Siempreviva from one of Severo Sarduy’s characters and the first Cuban literary journal, founded by Antonio Bachiller y Morales in 1838. That monthly publication, directed mainly to the youth of Havana, aimed to “express good ideas in a simple style, ideas that would otherwise never penetrate in the popular masses; …to stimulate, with short and scientific digressions, the effort of young people devoted to literature and science, and lastly, to publish our local observations on customs” (La Siempreviva 1838, 3). Like the 19th century publication, Café-teatro La Siempreviva performances were directed mainly at young people looking for a place that would grant them entry at a reduced price and that would enable the exchange of creative ideas and the debate on many other topics essential for artistic training and social critique.

They performed, accompanied by the improvisations of young musical artists, visual artists, and theater artists, who have always  been loyal followers of Nelda Castillo. The need for a space for professional-level artistic interaction in the Instituto Superior de Arte largely motivated the conception of the café-theater—a mode of interaction that nearly disappeared during the economic and social crisis of the 1990s. The performances in the café-theater were called Café-teatro La Siempreviva. Building on the effort to recover cultural memory, those involved took the name Siempreviva from one of Severo Sarduy’s characters and the first Cuban literary journal, founded by Antonio Bachiller y Morales in 1838. That monthly publication, directed mainly to the youth of Havana, aimed to “express good ideas in a simple style, ideas that would otherwise never penetrate in the popular masses; …to stimulate, with short and scientific digressions, the effort of young people devoted to literature and science, and lastly, to publish our local observations on customs” (La Siempreviva 1838, 3). Like the 19th century publication, Café-teatro La Siempreviva was directed mainly at young people looking for a place that would grant them entry at a reduced price and that would enable the exchange of creative ideas and the debate on other topics essential for artistic training and social critique.

been loyal followers of Nelda Castillo. The need for a space for professional-level artistic interaction in the Instituto Superior de Arte largely motivated the conception of the café-theater—a mode of interaction that nearly disappeared during the economic and social crisis of the 1990s. The performances in the café-theater were called Café-teatro La Siempreviva. Building on the effort to recover cultural memory, those involved took the name Siempreviva from one of Severo Sarduy’s characters and the first Cuban literary journal, founded by Antonio Bachiller y Morales in 1838. That monthly publication, directed mainly to the youth of Havana, aimed to “express good ideas in a simple style, ideas that would otherwise never penetrate in the popular masses; …to stimulate, with short and scientific digressions, the effort of young people devoted to literature and science, and lastly, to publish our local observations on customs” (La Siempreviva 1838, 3). Like the 19th century publication, Café-teatro La Siempreviva was directed mainly at young people looking for a place that would grant them entry at a reduced price and that would enable the exchange of creative ideas and the debate on other topics essential for artistic training and social critique.

In the 2004 series, some characters/beings of earlier works—Auxilio (Mariela Brito), Christ of the Rue Jacob/Sarduy (Eduardo Martínez), Socorro (Lorelis Amores)—were presented as performers who shared their histories in the live presence of the spectators.

Two of the characters/beings that would later appear as protagonists in the group’s first performances/interventions—The Accompanist (Mariela Brito) and Cubita (Lorelis Amores)—were born in the second café-theater (2004). The first one, baptized as Enriqueta, had her own number in Café-teatro La Siempreviva. Her performance as an accompanying pianist was inspired by real-life people who were well known to ISA’s students and professors. The starting point of this creation was a complete high-social-status mask. The staged vignette was a classic exercise of the grotesque in direct communication with the audience. The intensity and baleful glance of the pianist, as seen from the front, were in direct contrast with the torn dress through which we could see her naked back, including her rear end, not covered by underwear. The badge from the first congress of the Saiz Brothers Association, an organization that brings together young creators and artists from across the island, and a briefcase full of items for personal hygiene, coffee, and cigarettes from the basic food market available for nonconvertible Cuban pesos (CUP) [2] completed this image. The reselling of these household items established a social caricature highlighting the quotidian precariousness of music professionals.

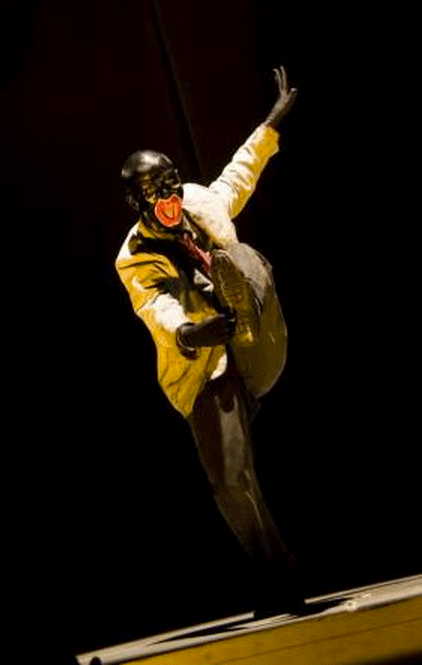

The Cubita character was first created to serve drinks in the intermissions of the Café performances. Following the traditions of Cuban vernacular that Nelda Castillo knows so well—she worked during the 1980s in the Teatro Musical de la Habana (Havana Musical Theater) with Carlos Pous, one of the renowned “negritos”[3]—Cubita wore blackface and a dress designed by the actress herself, tailored with the scraps of products that are only accessible in the Convertible Cuban Peso (CUC). Cubita called attention indirectly to the disadvantages faced by Afro-Cubans at the beginning of the 21st century. In this case, the group also voiced a critical reflection on the double-currency system, which would reappear in other works.

The Cubita character was first created to serve drinks in the intermissions of the Café performances. Following the traditions of Cuban vernacular that Nelda Castillo knows so well—she worked during the 1980s in the Teatro Musical de la Habana (Havana Musical Theater) with Carlos Pous, one of the renowned “negritos”[3]—Cubita wore blackface and a dress designed by the actress herself, tailored with the scraps of products that are only accessible in the Convertible Cuban Peso (CUC). Cubita called attention indirectly to the disadvantages faced by Afro-Cubans at the beginning of the 21st century. In this case, the group also voiced a critical reflection on the double-currency system, which would reappear in other works.

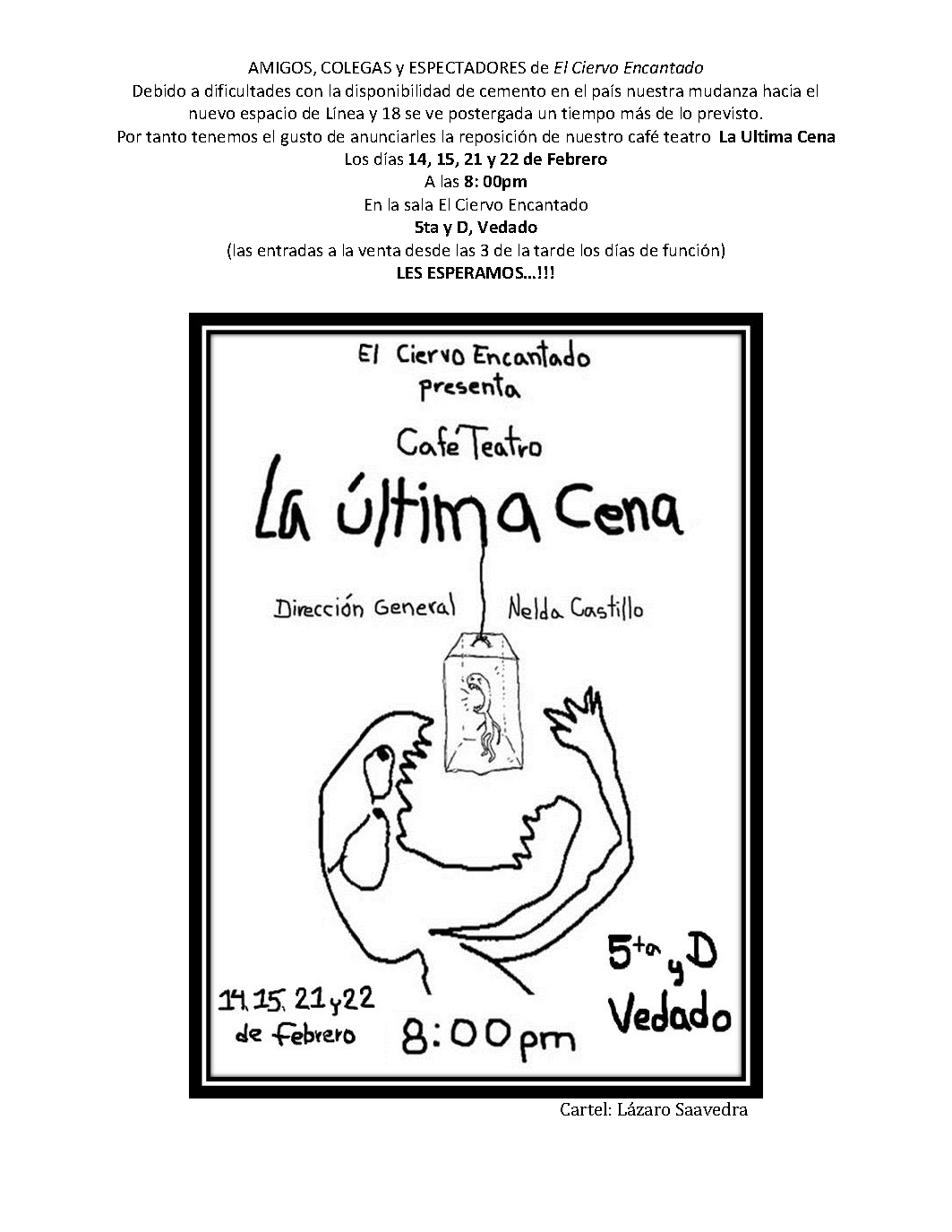

Café-Theater The Last Supper

February 14, 2014

The Chapel of El Ciervo Encantado, Havana, Cuba

In 2007, after their expulsion from the space created in ISA, the group found a new space—almost derelict, but more centrally located—in front of the Villalón Park in El Vedado neighborhood. The group constructed its new theater, the Chapel of the Ciervo Encantado, in the old chapel of the house where the Dominican Máximo Gómez—the general of the Cuban army in the wars of 1868 and 1895—passed away. To bid farewell to their former space, they once again chose the format of the café-theater, with a performance now entitled Café-teatro La última cena (Cafe-Theater The Last Supper). Ironically, despite its title, there was more than one performance of The Last Supper in the chapel. As the announcement that was circulated in February 2014 read: “Due to difficulties with the cement supply in the country, our relocation to our new space in the corner of Línea and 18th Street has been delayed longer than expected.” Once again, the performers transformed the chapel into a multi-purpose space for the convergence of all the arts. This café-theater was structured to include a variety of styles—from dance to music, performance, and visual art—which were interwoven among nine numbers performed by different members of the group. These unexpected couplings—lyrical song with rap or jazz, for example—were fused with an updated rereading of Cuban vernacular theater, in which characters with real life referents, icons of Cuban popular theater, and other beings gave their accounts of different aspects of contemporary reality.

On the porch, Martica Minipunto (Martha Luisa Henández) welcomed the public while rapping “Pragmatics of the Self,” a speech that mixes fragments of criticism, theoretical quotations, and self-referential passages. Rap serves as a parody to conceal and reveal social disorientation from a personal perspective characteristic of the artists from her generation—those called “los novísimos” (“the newest ones”).

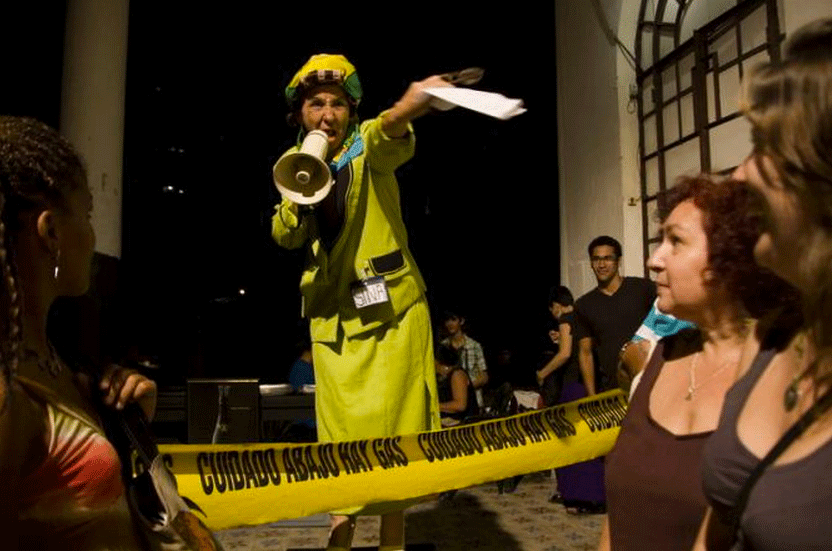

Mariela Brito, on her end, premiered a new character in the piece “Orden en el parque de los suspires” (“Order in the Park of Sighs”). Armed with her loudspeaker and wearing a badge of the US Interests Section (USIS), she acted as a doorwoman and organized the line of waiting spectators, whom she classified according to a ticket they had been given previously, just as people awaiting a US visa are classified. Divided into the categories of “Definitive Departure,” “Family Reunion,” “Political Asylum,” and “Lottery,” the audience members were placed in the position of thousands of Cubans seeking to migrate to the United States, the North American neighbor with which the island sustained a conflict that lasted for more than half a century (finally ending on 17 December 2014).

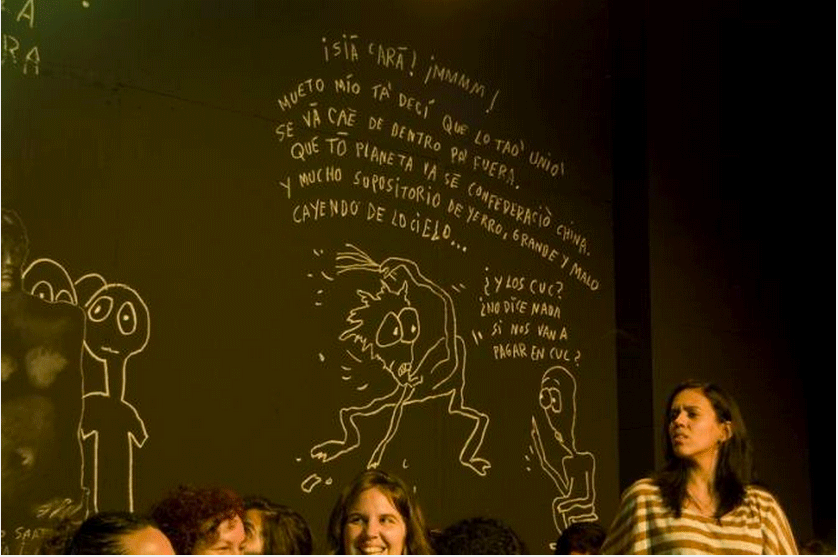

The drawings of Lázaro Saavedra (a collaborator of El Ciervo Encantado and the designer of the announcement for The Last Supper) transformed the walls of the café-theater. They are the same “cartoons” that, during 2012, offered us a weekly, sarcastic commentary on the political, social, and artistic reality of contemporary Cuba. The audience, seated in between the drawings and acting as co-protagonists of The Last Supper, shared this space in which they were able to question Cuban reality through humor and performance.

In “La Estrella” (“The Star”), the emcee of Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s Three Sad Tigers, dressed as Elvis Presley (Nelda Castillo) with a foreign-sounding accent, enters seeming a bit lost: he does not know if he is in the Tropicana cabaret or in some other place. “Showtime! Señoras y señores. Ladies and gentlemen.” Asking, like Miguel Matamoros and Severo Sarduy, “Where are the singers from?” Elvis leads the audience to a new inquiry on the margins of the nation.

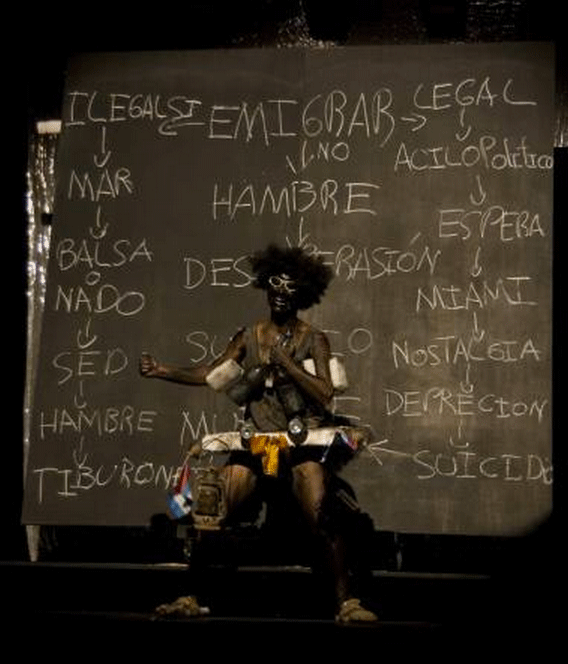

A balsero (literally “rafter,” but colloquially denoting a person who travels by raft from Cuba to Miami) played by Grisell Monzón calculates the probability of surviving once he takes to the sea in “Rumbo a la gloria” (“Going to the Glory”). Using sentences that s/he writes on a blackboard, this section of the performance is a tragicomic questioning of why contemporary Cuban emigration exists, transforming this performance into a space of reflection, critique, and analysis of problems in a humorous tone.

Guests Gabriela Burdsall and Luis Enrique Carricaburu, graduates of ISA and dancers of Danza Contemporánea de Cuba (Contemporary Dance of Cuba), demonstrate in their piece that there are no borders between dance and performance.

“El Negrito,” the blackface character of the Cuban vernacular who had previously appeared in Café-teatro La Siempreviva makes another appearance in “Tap Palobajo” to share with the audience a hilarious critique of the smuggling of prohibited goods, such as sex toys.

The café-theater closes with a parody of criticism itself. The actors of the group personify five contemporary Cuban critics—Omar Valiño (Daniel Romero), Yohayna Hernández (Grisell Monzón), Vivian Martínez Tabares (Mariela Brito), Jaime Gómez Triana (Abel Rojo), and Norge Espinosa Mendoza (Arnaldo Galván)—in a “roundtable discussion” that ends up being a monologue. With perfect outfits, physicality, and speech, each presents his or her opinion on the group’s artistic trajectory by choosing their favorite production of El Ciervo Encantado.

As with Café-teatro La Siempreviva 15 years earlier, The Last Supper inaugurated a space in which both emerging and renowned artists were equally welcome. Beyond fostering a dialogue with young students and professionals of the arts, the café-theaters created a place for the formation and development of actors—either members of the group or students of the several workshops Nelda Castillo taught—which broadened the reach of the collective’s cultural mission. Both café-theater pieces sought to recover a space for bohemian Cuban nightlife, which practically disappeared after the Revolutionary Offensive of 1968 closed down more than 900 small bars and businesses, considering them both—the space and the bohemian circles—politically incorrect (Espinosa Mendoza 2009, 19). However, in contrast with the bohemia of the 1950s and 1960s, El Ciervo Encantado’s café-theaters have been places for dialogue and creation, where the naturalized order is interrupted through the generation of a space of interaction by and for those marginalized from that order. The ability to informally share and co-create in a “simple” style ideas that are otherwise unspeakable in other places renders every instance of the café-theater into an event in which “that which should not be visible is made visible” (Rancière 2006, 30).

As with Café-teatro La Siempreviva 15 years earlier, The Last Supper inaugurated a space in which both emerging and renowned artists were equally welcome. Beyond fostering a dialogue with young students and professionals of the arts, the café-theaters created a place for the formation and development of actors—either members of the group or students of the several workshops Nelda Castillo taught—which broadened the reach of the collective’s cultural mission. Both café-theater pieces sought to recover a space for bohemian Cuban nightlife, which practically disappeared after the Revolutionary Offensive of 1968 closed down more than 900 small bars and businesses, considering them both—the space and the bohemian circles—politically incorrect (Espinosa Mendoza 2009, 19). However, in contrast with the bohemia of the 1950s and 1960s, El Ciervo Encantado’s café-theaters have been places for dialogue and creation, where the naturalized order is interrupted through the generation of a space of interaction by and for those marginalized from that order. The ability to informally share and co-create in a “simple” style ideas that are otherwise unspeakable in other places renders every instance of the café-theater into an event in which “that which should not be visible is made visible” (Rancière 2006, 30).

Works Cited

Espinosa Mendoza, Norge. 2009. “Las mascaras de la grisura: teatro, silencia y política cultural en la Cuba de los 70.” Paper presented at the Centro Teórico-Cultural Criterios, Havana, Cuba, January 20. https://www.criterios.es/pdf/10espinosamascarasgrisura.pdf.

Rancière, Jacques. 2006 Política, policía, democracia. Trad. María Emilia Tijou. Santiago de Chile: LOM ediciones.

[1] We use “beings” because, for this group, performance, just like theater, is “an event that occurs in the here and now, involving the organism of actor and spectators: a life experience and not an appearance, where the actors do not represent, they ‘are.’”

[2] Since 1994 there have been two currencies circulating in Cuba: the CUP, also known as the Cuban peso, in which Cubans receive their salaries and their pensions, and the CUC, or convertible Cuban peso, which is necessary to pay for most consumer goods. The CUC is nearly equivalent in value to the US dollar and can be exchanged for 24 Cuban pesos (CUP). This double currency system has resulted in great socioeconomic differences between those who can access the CUC (mainly those who work in tourism or receive family remittances from abroad) and the majority of the population, who can only access the national currency.

[3] The “negrito” is a stock character in the Cuban blackface tradition. See Jill Lane’s 2005 work Blackface Cuba, 1845–1895 for more on the history of this character.