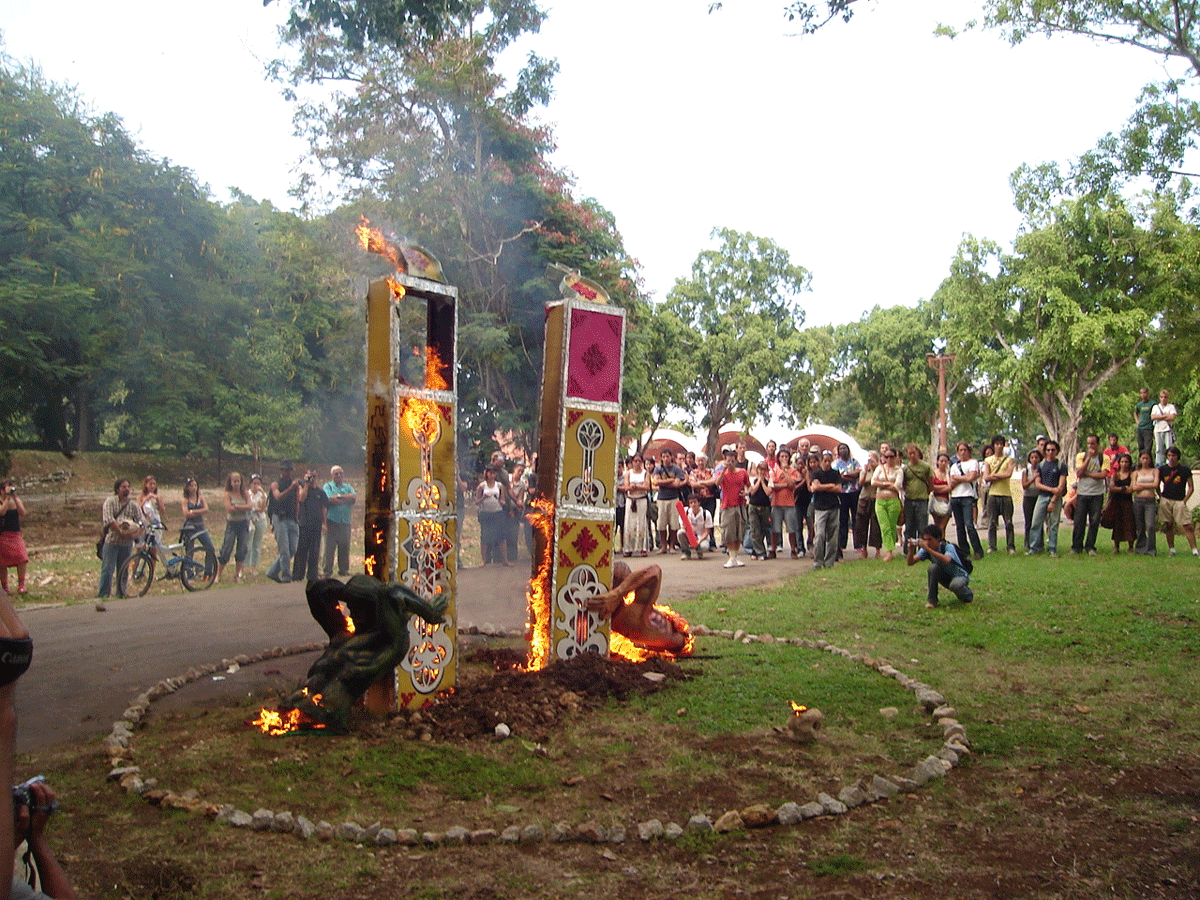

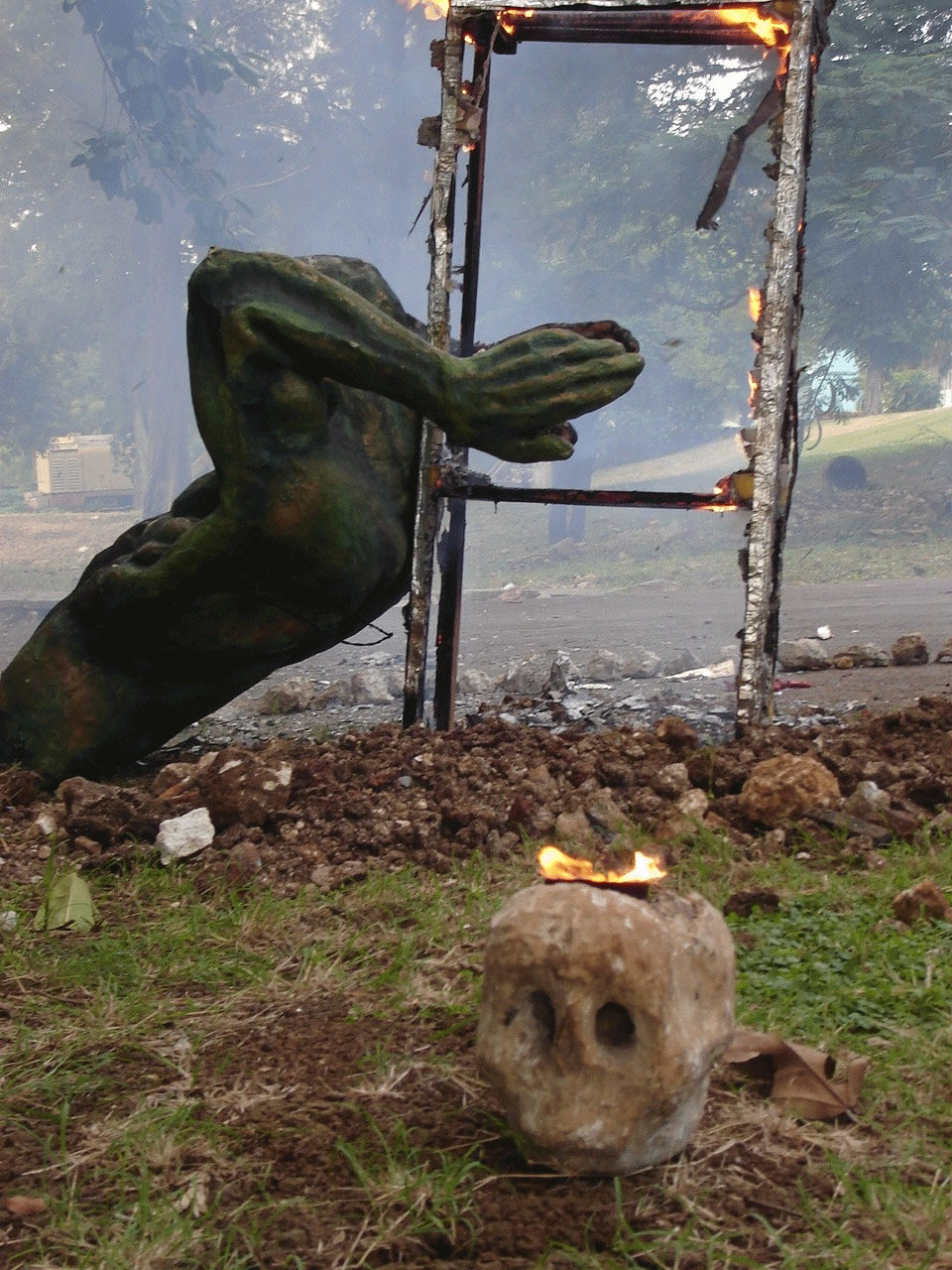

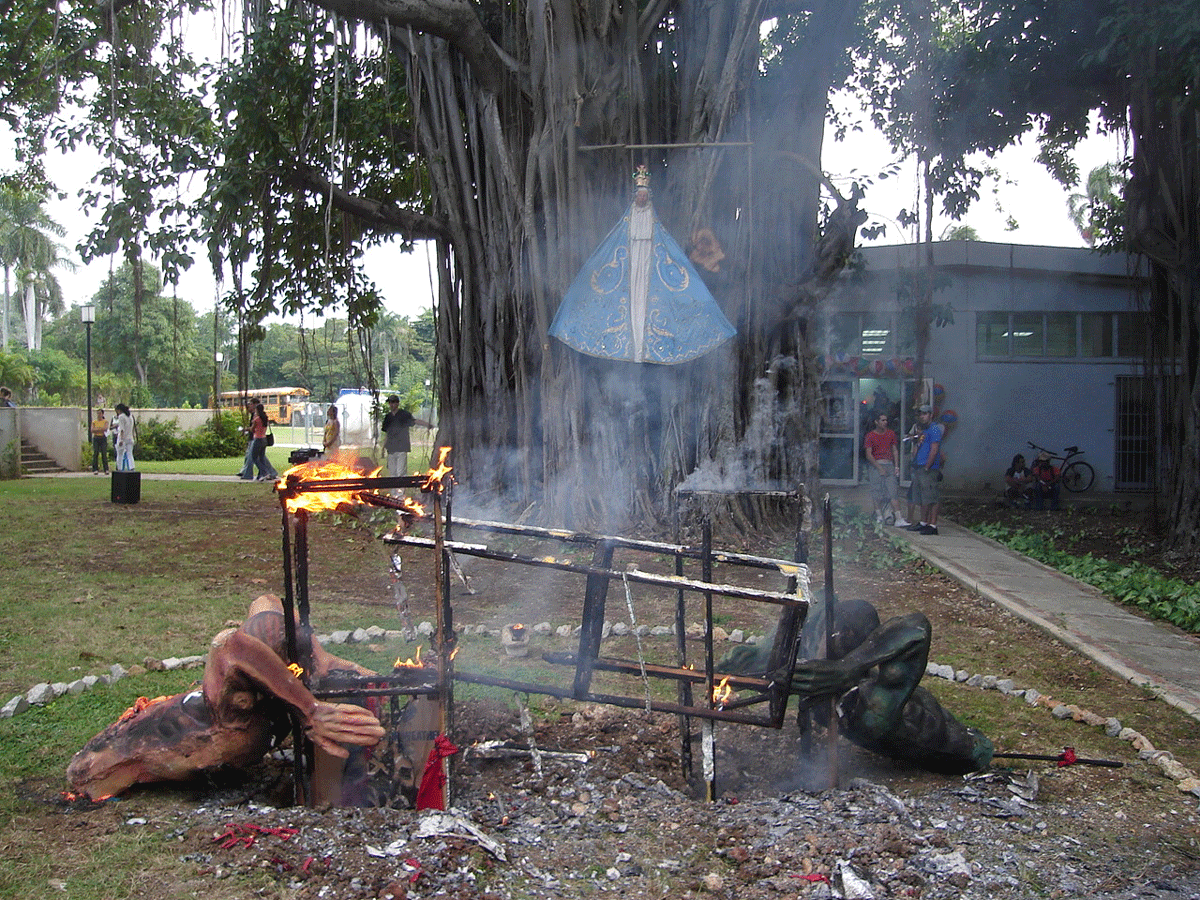

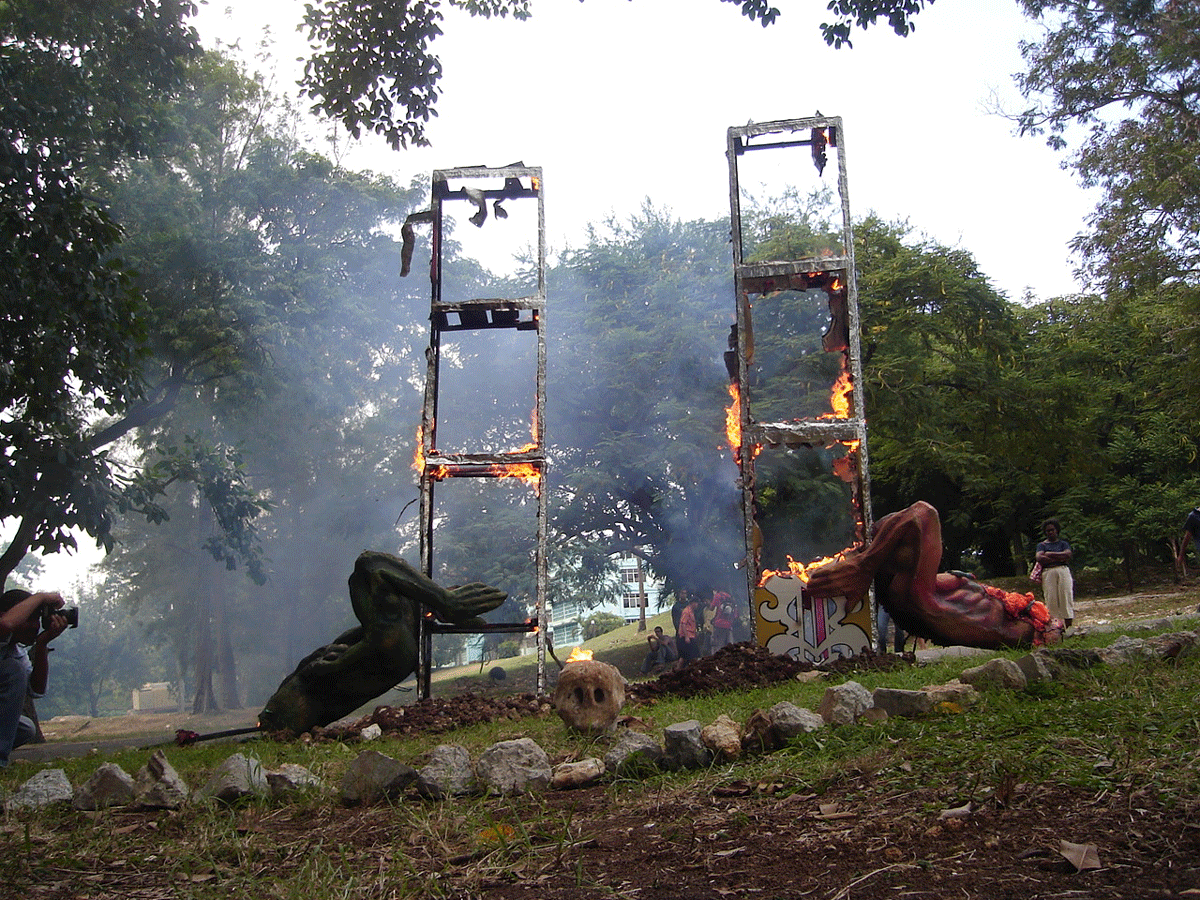

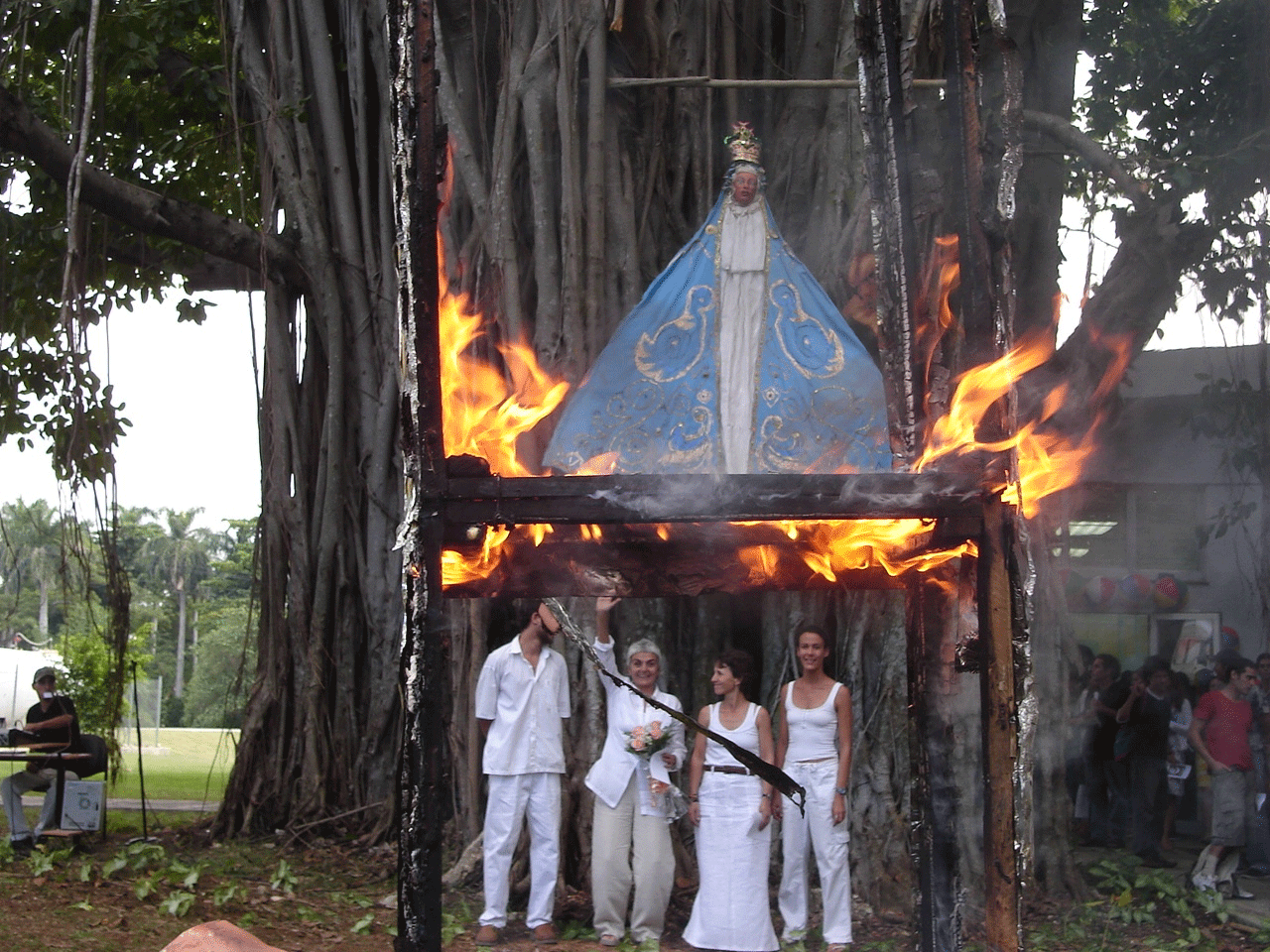

After 10 years of working with students at Havana’s University of the Arts, El Ciervo Encantado was informed that they needed to leave the premises they themselves had cleaned up, rebuilt, and transformed. Faced with the uncertainty of not knowing where they would go next, they took to the streets, moving to an outdoor space in the University to do performance/ritual Humo en las altas torres (Smoke in the High Towers), in which they burnt the props from their past productions. The group took the virgin statue from Visiones de la cubanosofía (Visions of Cubanosophy) and carried it in a procession from ISA’s Department of Visual Arts to the library, where a small exhibit about the last decade of their work was being shown. The performance started with the invocation/text, “Smoke in the High Towers,” officiated by Mariela Brito. The text, written by Nelda Castillo and interwoven with the images below, is an allegorical testimony of El Ciervo Encantado’s work with students and their community. The intertext is Esteban Borrero’s short story, “El ciervo encantado” (1905), in itself a historical allegory and a political satire of Cuba at the turn of the 20th century. This performance marked their exit from the stage; afterwards, they began working in public, open spaces and challenging cultural institutions in order to confront the specter of the 1970s in Cuban culture.[1]

Smoke in the High Towers

October 25, 2006

Instituto Superior del Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba

It has been more than 20,000 years, and the event can only interest those who track man’s past, those who dig through the earth to find idols and make a history for themselves. Lower, lower, reading layer by layer, page after page, the book that time, a perennial and betrayed witness, has left written in the great folio of the earth. The eternal misfortune that is the act of remembering. The horrific, circular walk through this site; it does not matter whether it is a temple in ruins or a crater, a house or a tomb. There, lower, lower, with the sea chopping at their backs, lives La Siempreviva (The Evergreen).

A strange caravan—it does not matter whether it is a procession, a conga line, a parade, a funeral march—was set in motion by the ringing of the bell. They had discovered the powerful reality of a door. The door of no departure. It does not open any path, nor does it close it. Step by step, the lamplighter illuminates the road. They head to the towers. They come from the depths: dark and humid basements where innumerable treasures are guarded. Their clothes are threadbare, the remains of a glorious past, salvaged from a catastrophe, the dregs of a hurricane. From a strip of lace, a city can be rebuilt; from a sequin, a carnival.

They are crazy, but not stupid.

They carry the fragile image of a forgotten dream, rescued from the ruins of memory.

They bear the banner of Happiness. And they yell:

“El Ciervo Encantado has died!!!”

Smoke in the towers, smoke in the high towers.

You must jump from the bed with the firm conviction that your teeth have grown and that your heart will emerge from your mouth.

“El Ciervo Encantado has died?” ask those who, until yesterday, did not allow themselves to dance when the flute played or to cry when sad songs were sung.

Yes, El Ciervo Encantado has died. But that happened more than 20,000 years ago, because of the foolishness of its hunters. Its tomb is the whole island, plowed in the sea. Its corpse has been scattered along the length and width of the 111,111 square kilometers of the national territory.

One will have to attempt a new and tireless crusade to retrieve its grave from the power of the country’s enemies: graduates, dukes, barbers, priests, and the coolies of the convertible pesos.

El Ciervo Encantado has died, has chosen its own death, has dreamed the arrow, the sword, the bolt of lightning, the thunderclap that will smash up and down the eardrum of the sleepers.

Smoke in the towers, smoke in the high towers.

No matter whether you are from a sugarcane factory, a cathedral, a boat, or a crematorium. You must leap from the bed. You must scratch. Now the description of a tiger or the wooden skeleton of a horse’s head does not proceed. It is the god of fire itself. Fire. We are going to play at the truth.

The flames demolish the temple again. The mask falls, the passion is exposed. No need to inhabit a tomb to be reborn, so that the reconstruction is truthful.

The incessant work of man has always been to make himself a house, and a house is also a culture. But the times are of contempt and of catacombs. And when the fatherland is in danger, everything to the fire…

Living outdoors to feel the pure and suffered rain in silence, the mysterious, tropical drizzle.

El Ciervo Encantado has died, and the serpent python does not swallow it. It ascends by its antlers like the Tree of Life.

The strange caravan resolves on an insane mission—as crazy as that of the Apostle who dreamed of an island of poetry: to catch the magical animal, which vanishes into thin air, triumphant and mocking.

And they yell:

“O my mother, give the yoke to me so that, standing tall on it, the star that illuminates and kills will shine even brighter. And there where the tomb lies, there is madness, and from there, the star will rise again, brilliant and resonant on its path to the heavens. From a death until another death, I prepare myself to awaken.

El Ciervo Encantado has died.

Long live El Ciervo!!!”

[1] For information on the group’s work during this first phase, as well as their pilgrimage, see the documentaries Vía Crucis del ciervo (https://ctda.library.miami.edu/digitalobject/15795) and Mudanza (https://ctda.library.miami.edu/digitalobject/15794).