In January 2007, Cuban TV broadcast a program paying homage to Luis Pavón Tamayo, the director of the National Council on Culture from 1971 to 1976 and the censor responsible for the period euphemistically referred to in Cuba as the “gray half-decade,” which saw the persecution of hundreds of artists due to their “improper conduct” or their homosexuality. When he viewed the homage to Pavón, the writer Jorge Ángel Pérez wrote an email to several artists maintaining that “Luis Pavón, one of the most horrid and atrocious characters in the history of Cuban culture, is receiving lavish praise from Cubavisión’s Impronta program.”[1] His email prompted a “little email war” in which hundreds of artists, writers, and intellectuals, both inside and outside of Cuba, voiced their opinions on Pavón, discussed the possible meaning of his televised feature at that specific moment (Raúl Castro had been named interim president while Fidel Castro convalesced), and debated what intellectuals needed do to prevent the return of a hard-line cultural policy along the lines of the 1970s. In response, Desiderio Navarro, the director of the Centro Teórico-Cultural Criterios and the editor of the journal Criterios organized the conference cycle “The Cultural Policy of the Revolutionary Period: Memory and Reflection.” Many of the victims of the Pavonato (as the “gray half-decade” has also been called) participated, along with some younger people who had not been born yet in the 1970s. There were many who could not attend the conference due to lack of space or invitation—especially young people who did not belong to any organization and those branded as dissidents in Cuba.[2] These conferences were interpreted in different ways: for some, they were a way of “ensuring that the snowball follows the path we have chosen for it, not to let it deviate so that, instead of clearing the space of residues, it destroys with its weight everything we have already achieved” (desdecuba.com). Others considered them a way of domesticating the open debate that unfolded spontaneously on the Internet.[3]

For Nelda Castillo, “the debate was reduced to something byzantine and inconsequential because there was no real reflection on the problem and, therefore, no solution” (Pérez Vera 2008, 40). It is in this context that El Ciervo Encantado participated in that moment of memorialization and reflection on the specter of the 1970s, through staging the performances Enriqueta al debate intelectual (Enriqueta to the Intellectual Debate) (2007), Cubita luchando la firmeza (Cubita’s Adjudication Struggle) (2007), and La lista de Schindler (Schindler’s List) (2009). In all of these performances, the being/character created by the performer presented herself in public space wearing several different masks, aiming to participate not so much in the discussion of what had happened in the gray half-decade, but rather what was happening in 2007.

Enriqueta to the Intellectual Debate

Mariela Brito

23 February 2007

School of Music, Instituto Superior de Arte, Havana

Enriqueta had already appeared in the café-theaters as the piano teacher, elegant but lacking even the basic resources to mend her torn dress. Now, she presented herself in her place of work, the Instituto Superior de Arte, during the assembly organized for the young people who had been left out of the first conference.[4] The “Criterios” Theoretical-Cultural Center and the Saiz Brothers Association invited young students to the “Workshop on the Cultural Policies of the Revolution.” More than 200 young people gathered and expressed their discomfort regarding the issues at hand. Even though Enriqueta did not speak a word, her actions and interventions in the forum said more than anything expressed in the forum itself: socioeconomic inequality and censorship are not things of the past.

Cubita Fighting la Firmeza

Lorelis Damores

Intervention in the lecture by Mario Coyula, “The Bitter Trinquennial and the Dystopian City: Autopsy of a Utopia”

19 March 2007

School of Music, Instituto Superior de Arte, Havana

At a March 2007 lecture, Cubita, who sold soft drinks payable in national currency at the café-theater, presented herself as a woman residing in a low-income neighborhood who wanted to move out. But in order to move, she needed a legal document referred to as la firmeza, one of the documents that the local housing office issues.[5] Upon hearing news of the lecture “El trinquenio amargo y la ciudad distópica: autopsia de una utopia” (“The Bitter Trinquennial and the Dystopian City: Autopsy of a Utopia”) by architect Mario Coyula, Cubita hoped to attend, as the cream of the crop of Cuban architecture would be there. She wanted to receive their support, since they would have sufficient power, authority, and influence to help her obtain la firmeza and enable her longed-for move out of the marginal zone where she lived. The audience and some employees did not know how to react when Cubita asked Yoandri, the community architect, to help her resolve her problem. Cubita was carrying a sign with a flag, and it was through her sign and her multiple interactions with the audience that she put forward her issue: “Cubita is asking for something very specific: an exchange title for payment currency. She offers her salary, but demands at least 50 percent of it in CUC. This character does not want to hear anything because what she needs is this exchange title to resolve her problems, to feed her children. She says, ‘Do not speak more about the city that is falling apart when there is a problem as basic as the fact that I cannot even live off of my wage’” (Pérez Vera 2008, 40). With the performance in the space where Coyula eventually spoke, Cubita reminded the audience about the marginalized victims of the system—the Afro-Cubans and the socioeconomically disadvantaged who barely survive from what they can scoop up in the trash. As Nelda Castillo rightly notes, “When we are talking about the way in which you scrape a living, how you feed your children or your family, it makes no sense to talk of the architectural disposition of the city” (Pérez Vera 2008, 40). Cubita did not obtain anything concrete, but she at least received some winks and knowing smiles that keep her hopes for change alive. Most importantly, she embodied and gave a face to the dystopia that Coyula was discussing with intellectuals behind closed doors: “The city is ever more dystopian… We see ourselves reflected more and more in a cruel mirror that reveals a withered face, animated long ago by the utopia convoked in its ideal no-place” (2007, 21). In other words, the audience that day must have seen in Cubita the specular and spectacular image of themselves.

Schindler’s List

Intervention in the lecture by Norge Espinosa, “The Masks of Grayness: Theater, Silence, and Cultural Policy in the 70s”

20 January 2009

Criterios Theoretical-Cultural Center, Havana

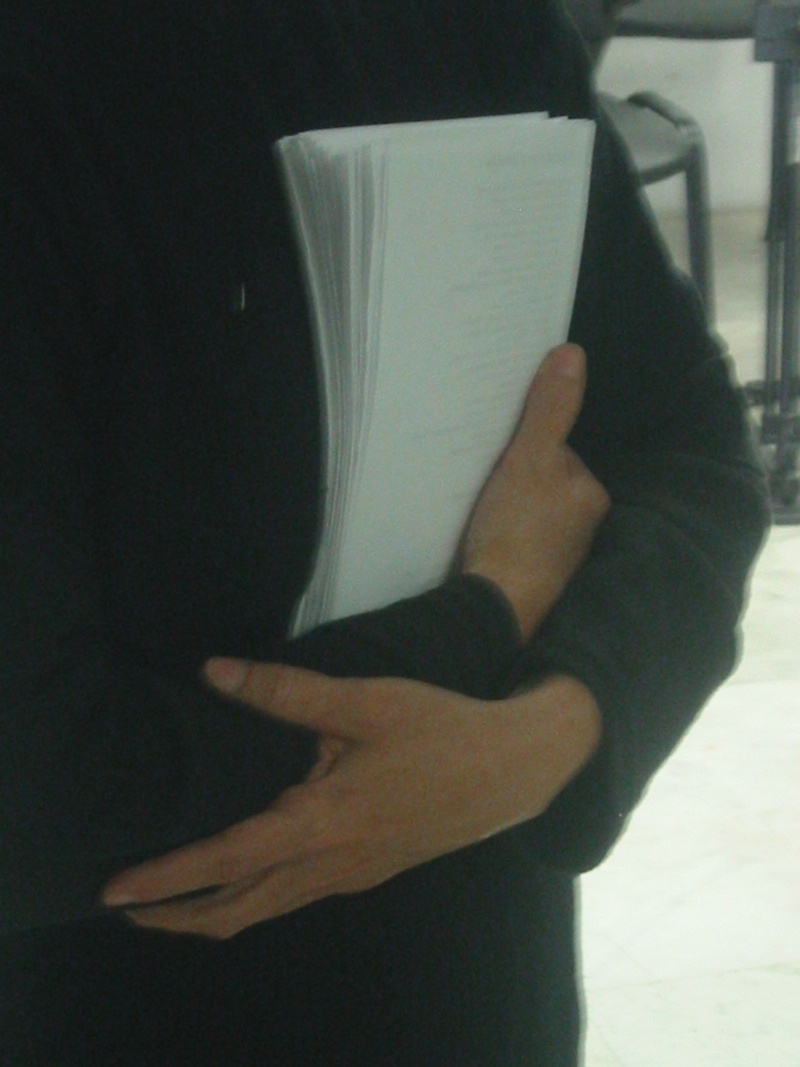

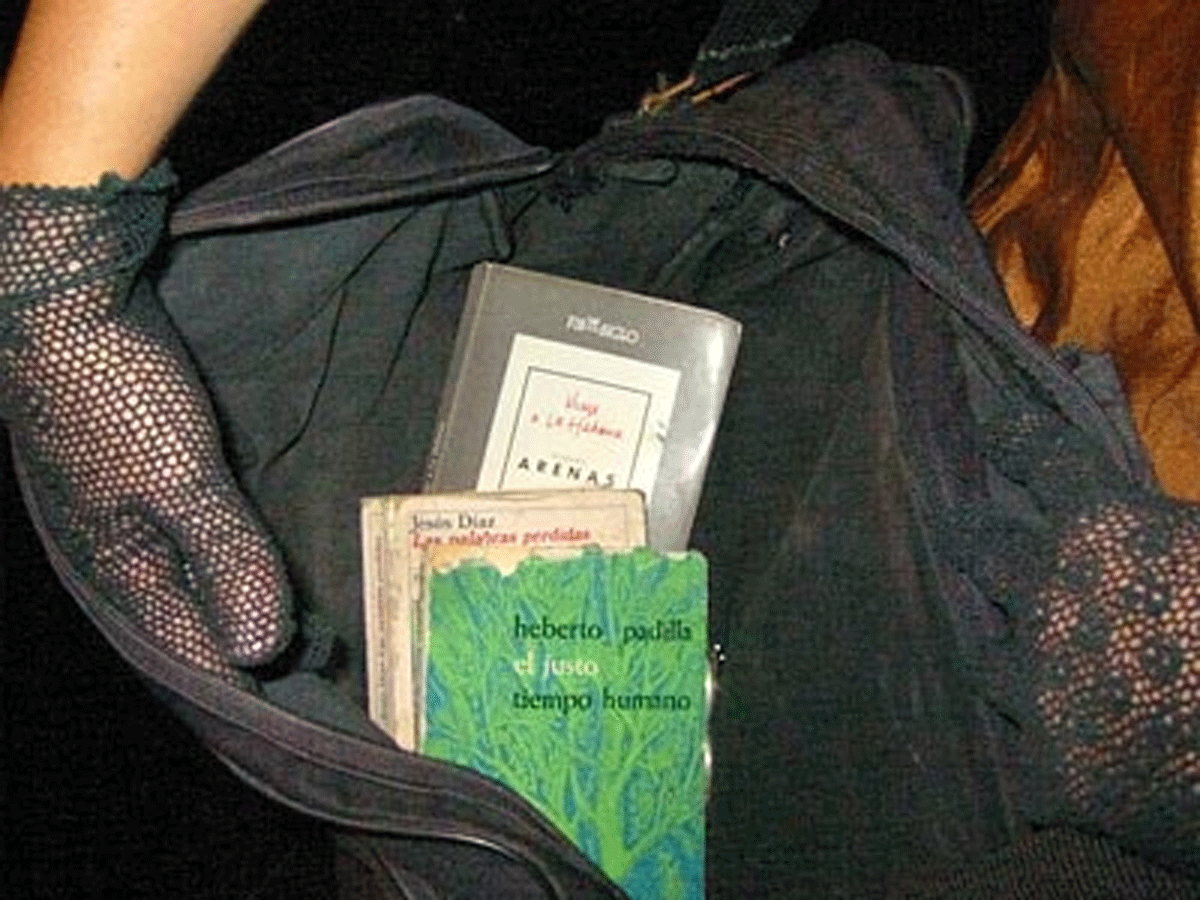

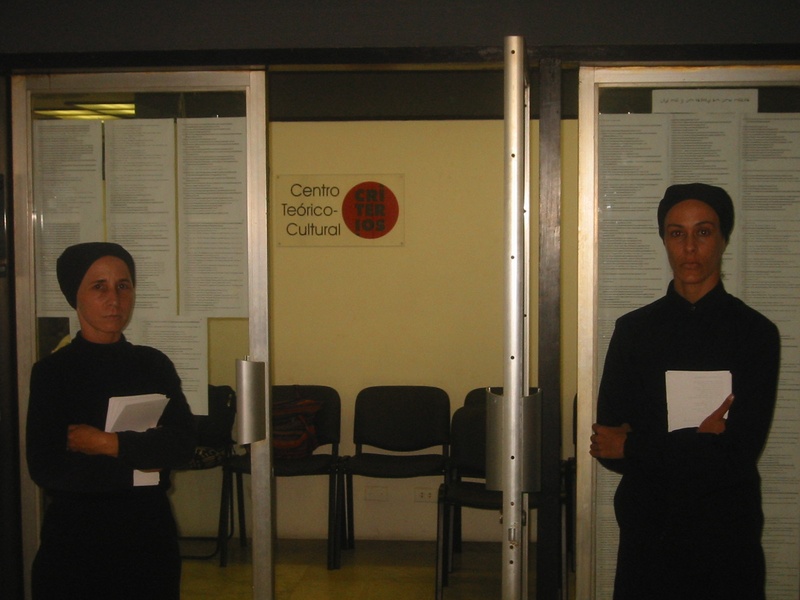

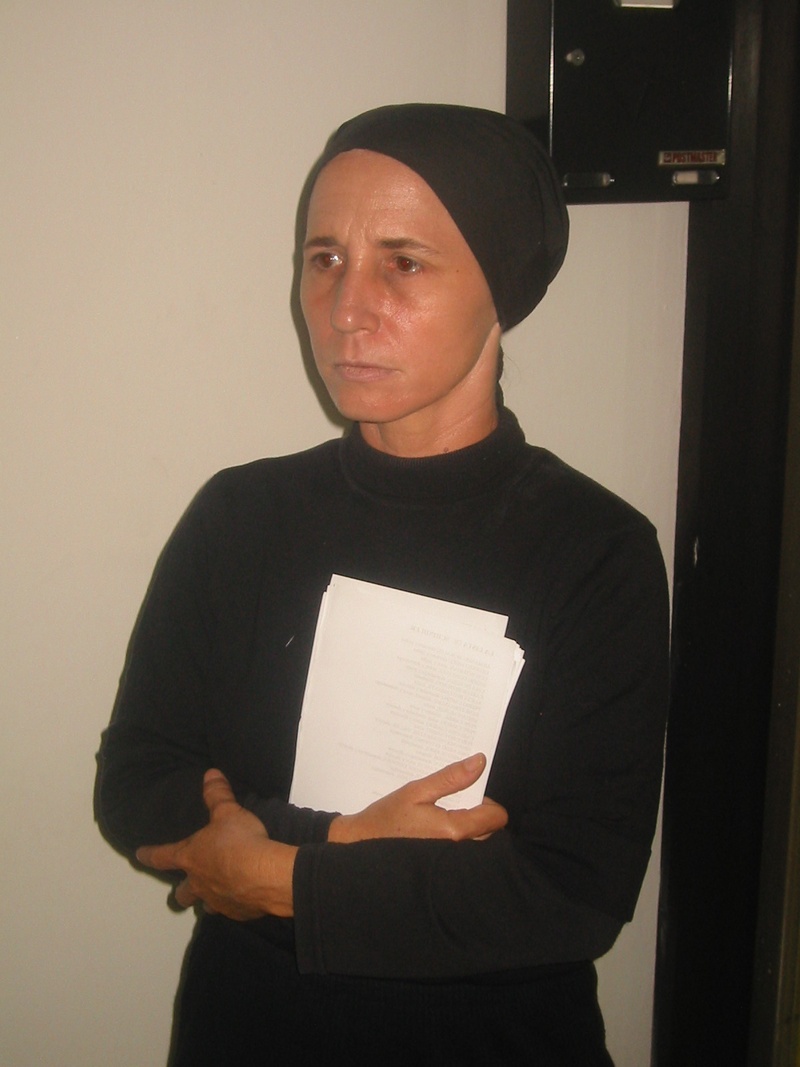

In Schindler’s List, staged two years after Pavón’s feature on TV, Mariela Brito and Lorelis Amores, assuming the masks of integrity and pain visible in the images of the millions of victims of the holocaust, stood guard in the entrance to the room in the Criterios Theoretic-Cultural Center, where Norge Espinosa Mendoza would read his lecture. As guardians of memory, they handed each visitor a list with the names of the artists who were victims of the parametración (a Cuban equivalent of black-listing).[6] They were not aware of the content of Norge Espinosa’s presentation, which argued: “The black-list is a kind of open secret, and there is no dearth of those who, in the current context, would want to add their name to it, pretending to have been the victim of a persecution which we have taken so long to denounce” (2009, 35). The performance subtly denounced and named hundreds of victims of the blacklisting. I do not know whether they had previously read Victor Fowler’s email, in which the critic noted that “in the end, no matter how much pain it may have caused, we are not dealing here with Adolf Eichmann organizing ‘the final solution’” (desdecuba.com) or the text in which Abelardo Mena suggested the creation of a Black Book of the Pavonato’s Practices of Cultural Violence, where the names of all the victims and perpetrators would be catalogued to promote a “conceptual dismantling of the implacable ‘social engineering’ that the Revolution implanted in the country” (desdecuba.com). What is undeniable is that El Ciervo Encantado knew how to performatively intervene in a public debate rendered semi-private by unpacking the category of victim into a list of individual subjects, recording the names of all the artists who were disappeared from public space during the 1970s.

ARMANDO MORALES, titiritero y pintor (puppeteer and painter)

ERNESTO BRIEL, titiritero y pintor (puppeteer and painter)

LUIS INTERIÁN, actor y juglar (actor and troubadour)

INGRIG GONZÁLEZ, actriz y dramaturga (actress and playwright)

LINA DE FERIA, dramaturga y poeta (playwright and poet)

CARLOS REPILADO, diseñador (designer)

ALICIA BUSTAMANTE, actriz (actress)

PEDRO CASTRO, diseñador y director (designer and director)

RENÉ FERNANDEZ, director, actor y dramaturgo (actor and playwright)

MIRIAM MUÑOZ, actriz (actress)

PEPE CARRIL, titiritero y actor (puppeteer and actor)

PEPE CAMEJO, actor, diseñador y director (actor, designer and director)

CARUCHA CAMEJO, actriz y directora (actress and director)

PERUCHO CAMEJO, actor (actor)

ARMANDO SUAREZ DEL VILLAR, director (director)

ABELARDO ESTORINO, dramaturgo (playwright)

RAMIRO GUERRA, coreógrafo (choreographer)

PEPE SANTOS, director (director)

JOSÉ MILIAN, dramaturgo y director (playwright and director)

ROBERTO BLANCO, actor y director (actor and director)

EUGENIO HERNANDEZ ESPINOSA, dramaturgo y director (playwright and director)

TOMÁS GONZALEZ, dramaturgo (playwright)

GERARDO FULLEDA LEÓN, dramaturgo (playwright)

MARIO GONZALEZ, actor (actor)

ULISES GARCIA, actor (actor)

PANCHO GARCIA, actor (actor)

VIRGILIO PIÑERA, dramaturgo y poeta (playwright and poet)

ANTÓN ARRUFAT, dramaturgo (playwright)

SANTIAGO RUIZ, dramaturgo (playwright)

JOSÉ MARIO, poeta y dramaturgo (poet and playwright)

BERTA MARTINEZ, actriz y directora (actress and director)

DURING THE 5, 10, 11, OR MORE YEARS OF PUNISHMENT, THEY WERE GIVEN THE OPPORTUNITY TO WORK AS WHAT?

BUILDERS, FARMERS, MUNICIPAL LIBRARIANS, HOUSE PAINTERS, TRANSLATORS, PRISONERS, CHORUS OF EXTRAS, MATCHBOX FACTORY WORKERS, WAIT AT HOME, CROCODILE HUNTERS, EXILES, WORKERS IN THE PAPER BAG FACTORY, ASSEMBLY LINE WORKERS, GRAVEDIGGERS, PSYCHIATRIC PATIENTS.

At the conference, Espinosa Mendoza concluded by referring to the mask as an image: “I am learning, thanks to them [the blacklisted artists he had interviewed for his study] to recognize their faces as opposed to the masks over the grayness” (2009, 51). A skillful follower of El Ciervo Encantado, his lecture unmasked the the cultural policy and the “masks of grayness” of the period, mirroring El Ciervo Encantado’s approach to the mask. Each performance serves the group as a journey of initiation and as a means to recapture memory and to penetrate into the most traumatic zones of the Cuban past and present. This performative research entails a search for a superior level of expression on the part of the actor/performer. Through a psychophysical training, each actor proposes a mask through which she will connect with the world without annihilating the artist who lends her body and energy for the creation of an extraordinary reality (Gómez Triana 2012). For the group, the mask is not just the object that one wears to cover one’s face, but also the mask that the very body of the performer creates to cover/hide the personality of the actor and, in the words of Castillo, serves “as a corkscrew, to spray out that impulse, that which is dormant, that which you really are” (Pérez Vera 2008, 34). That mask is dress and makeup as much as it is voice, gesture, and pose. It implies, moreover, a specific work with the energy of the performer. With their performances in public space—in the doorways to those closed rooms of the intelligentsia—Mariela/Enriqueta, Lorelis/Cubita, Mariela, Mariela-Lorelis/survivors (of Pavón), and Nelda remain alongside all those left out of the debate, the subjects who have no place within the distribution of the sensible in contemporary Cuban cultural politics.[7] It is precisely in the convergence in the same space of those who distribute roles and those who refuse the place assigned to them in the distribution and in the mask/pose of the performer that reveals what the rest pretend or prefer not to see that I read the political impulse in El Ciervo Encantado’s performances.[8]

Works Cited

Arango, Arturo. 2007. “Pasar por joven (con notas al pie).” Paper presented at the Instituto Superior de Arte, Havana, Cuba. https://www.criterios.es/pdf/arangopasarporjoven.pdf.

—. 2010. “Cuba, los intelectuales ante un futuro que ya es presente,” Temas 64 (Oct-Dec. 2010): 80-90.

Gómez Triana, Jaime. 2004. “Un texto quimérico. Introducción a Pájaros de la playa.” Tablas 76.3 (Jul-Sept, 2004): ii-v.

Núñez Fernández, Ricardo. 2008. “La Permuta: An Effective Instrument for Housing Transactions in Cuba.” IHS Working Papers 19 (2008). Rotterdam: Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies. https://www.ihs.nl/fileadmin/ASSETS/ihs/IHS_Publication/IHS_Working_Paper/IHS_WP_019_La_Permuta_2008.pdf.

Pérez Vera, Amarilis. 2008. “Nelda Castillo: composiciones del cuerpo para el alma.” Tablas 58.1 (Jan-March): 33-40.

Ponte, Antonio José. 2014. Villa Marista en plata: arte, política, nuevas tecnologías. Madrid: Editorial Hypermedia. https://cubanuestra2eu.wordpress.com/2014/10/28/editorial-hypermedia-informa-sobre-concurso-y-libro/.

[1] The cited emails were edited in a collection published by cuba.com/polemica. As of 2015, the collection had been taken offline.

[2] The note announcing Ambrosio Fornet’s first conference and the rest of his cycle stated: “Aiming to guarantee a place for our writers, artists, and intellectuals in general in the still limited space, we have decided to reserve ourselves the right of entry through invitations that will be sent to members of UNEAC, AHS, UNHIC; professors and students of ICA, the Department of Art, and the Departments of Literature and Social Communication of UH; researchers from the Social Science Council of CITMA and the Martin Luther King Center, as well as specialists and cadres of ICRT and institutions of the Ministry of Culture.” The crowd that was left out of the conference waited until nearly midnight and enacted its own performance, shouting the slogan “Desiderio, Desiderio, listen to my Criterio.”

[3] For an analysis of the debate, see Arango 2007 and Ponte 2014.

[4] For an analysis of the meeting and the text see Arango 2010.

[5] Núñez Fernandez elaborates a clarifying study on the process of exchange titles (permuta) in Cuba in his 2008 study.

[6] This list had been preceded by a previous list they prepared for the performance “Ausencia Justificada” (“Justified Absence”).

[7] “All of us who have been close to Nelda know that both in her rehearsals and in her performances, she personally embodies the continuum of actions that her actors are enacting in front of her, from the standpoint of a seeming concentration of space, but with an absolute intensity.” (Gómez Triana 2004, v).

[8] Arango himself reads the occupation of spaces as an active intervention, following Edward Said’s terminology: “In the field of culture, the majority of young Cuban writers and artists remain today in a permanent and tense negotiation with institutional spaces, always bordering the limits of what is permissible. Faced with institutions, the artists no longer occupy a subordinate position, and frequently it is the institutions that are forced to be on the defensive.” (2010, 87).