The group has also made an effort to occupy public space in fine art galleries, collaborating with national and international artists and erasing the borderlines between visual arts, performance, and video art. We will only concern ourselves here with the performances in which the group has intervened in public space.[1]

Justified Absence

Mariela Brito, Lorelis Amores, Eduardo Martínez

Intervention in the exhibition The 80s Are Gone by artist Moisés Finalé

7 July, 2007

Servando Cabrera Gallery, Havana, Cuba

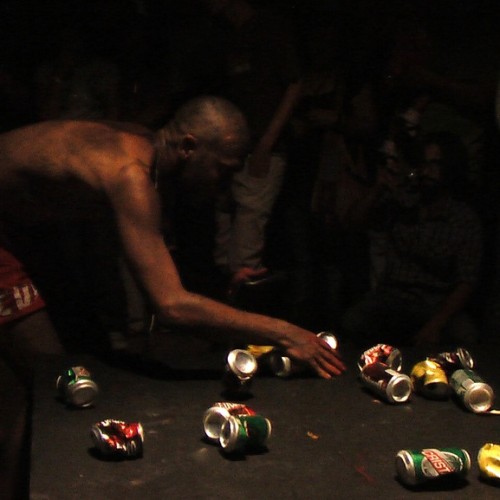

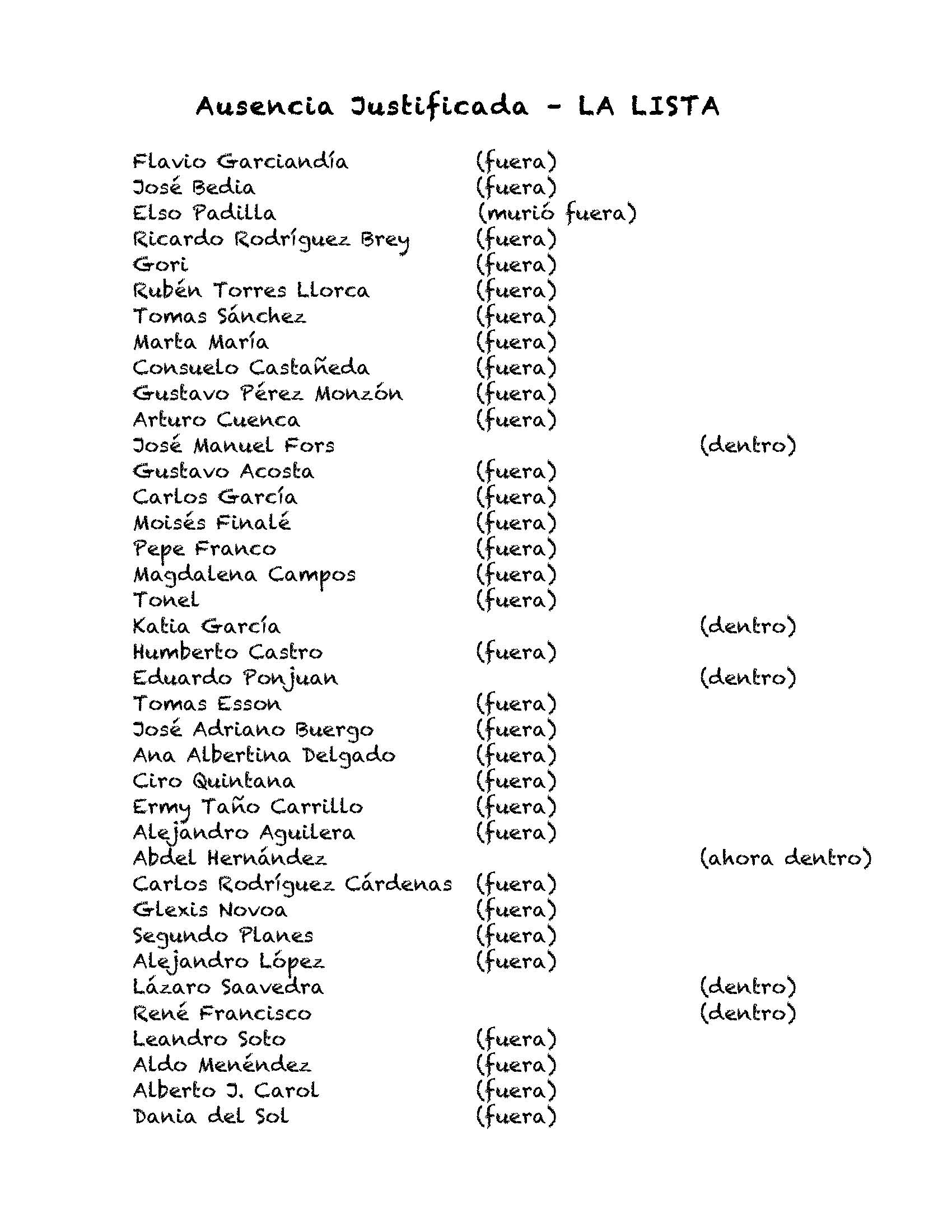

Ausencia justificada (Justified absence) is the title of their intervention in the 2007 Moisés Finalé show Se fueron los 80 (The 80s are Gone). With that exhibition, Finalé—an artist who has lived in France since the late 1980s—sought to put an end to the myth of the golden 1980s in Cuban visual arts, a decade which began for him with Volumen Uno and ended with the cancellation of his exhibition in the Castillo de la Fuerza, his last show in Cuba.[2] One of the important pieces in the show was a wooden trunk in which people could deposit an object that represented the 1980s. In that suitcase/coffin/reliquary (Crespo 2008) the audience, co-authors of the installation, deposited (made an offering of?) everything from a Sputnik magazine to a seal commemorating Arnaldo Tamayo, the first Cuban/Latin American to travel to outer space.[3]

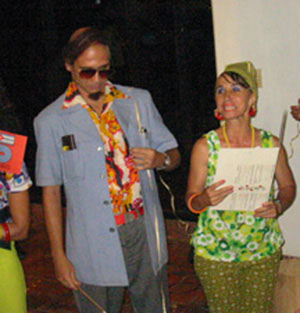

To this shipwreck of the arc of the 1980s, El Ciervo Encantado brought the absent protagonists who had no place reserved for them in this recounting: the émigré artists. To do so, they transformed the gallery into a work center and the exhibit into an emulation of a proletarian workday. They embodied three archetypal characters of revolutionary rhetoric: the comrades José Manuel Gutiérrez/Eduardo Martínez and Chela Domínguez/Mariela Brito, representatives of the National Secretariat, and the student Marilin Gutiérrez Domínguez/Lorelis Amores. The excuse for the gathering was an award ceremony for the country’s most outstanding artist collectives competing that year. Among the winners, the Artistic Brigade The Cuban 80s was honored. It was one of the first in the country to fulfill its plan for production.

They brought along a huge banner with the list of the most important artists of the 1980s. After reading a notice prepared for the moment, they called roll to confirm the absent artists and to acknowledge the best known of those present: Moisés Finlay Adeco/Moisés Finalé.

Chela delivered a reading of the Final Act with the results of the mock court. Moisés Finlay Aldeco received the certificate of recognition on behalf of Brigada Artística.

The act concluded with a healthy recreational activity organized by the student winner of the national gameshow Mi amigo el Machete (My Friend Machete), Marilin Gutiérrez Domínguez. It also included an exchange of gifts organized among all the collectives with the goal of strengthening the ties among workers of different sectors.

The performance parodied the acts characteristic of a once triumphalist labor rhetoric, with the presence of the comrades/masks and their gestures, acts, and words serving to reveal the “acts and behaviors that appear as increasingly false, threatening, and emptied of meaning in our own day” (Pérez Vera 2011, 48). It also worked as an exorcism of sorts by highlighting the series of attitudes displayed by the audience hearing the roll-call, “from those who knew those names perfectly well and the reasons why they had left or had been forced to leave (justifying their absence), to those who could not recognize exactly all the names in the list but ‘read’ the importance or significance of what was happening precisely because of the labor rhetoric and the ‘official act’ format, the repetition of a performativity that is exclusive of power (the platform, the exhortation, the awards) that the audience recognized very well” (Fundora Castro 2014).[4] Ultimately, El Ciervo named all those who left in the 1980s. By individualizing every artist, the performance vindicated those who were absent and publicly recognized their absence as more than justified.

The performance parodied the acts characteristic of a once triumphalist labor rhetoric, with the presence of the comrades/masks and their gestures, acts, and words serving to reveal the “acts and behaviors that appear as increasingly false, threatening, and emptied of meaning in our own day” (Pérez Vera 2011, 48). It also worked as an exorcism of sorts by highlighting the series of attitudes displayed by the audience hearing the roll-call, “from those who knew those names perfectly well and the reasons why they had left or had been forced to leave (justifying their absence), to those who could not recognize exactly all the names in the list but ‘read’ the importance or significance of what was happening precisely because of the labor rhetoric and the ‘official act’ format, the repetition of a performativity that is exclusive of power (the platform, the exhortation, the awards) that the audience recognized very well” (Fundora Castro 2014).[4] Ultimately, El Ciervo named all those who left in the 1980s. By individualizing every artist, the performance vindicated those who were absent and publicly recognized their absence as more than justified.

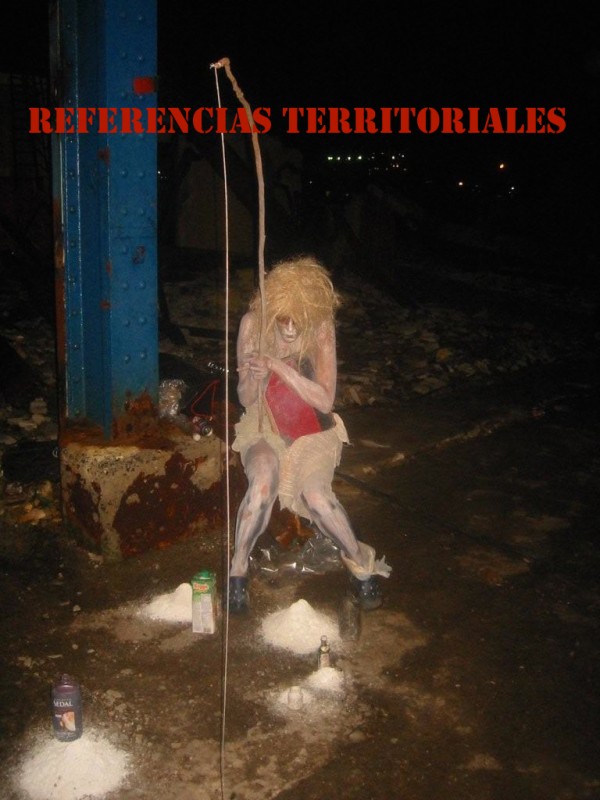

Territorial References

Lorelis Amores

5 August, 2008

Avenida del Puerto, Havana, Cuba

In 2008, a group of independent artists, including several visual art students from ISA, decided to put together an exhibition entitled “Referencias territoriales” (“Territorial References”) in an abandoned pier in the Avenida del Puerto. These young artists, conscious that the National Council on Fine Arts wields the power to decide where exhibits are held, had opted to locate themselves “on the margins of the conventional legitimizing circuits of ‘Cuban art’ and ‘national culture’” (Casanueva y González). The participating artists shared a conception of art as a representation of real situations based on their own personal experiences. It was therefore not a coincidence that the coordinator invited El Ciervo Encantado to participate in the exhibit, although the invitation was later withdrawn for unknown reasons. Nonetheless, in spite of the withdrawn invitation, the group “invaded” the exhibit the night of the opening with the performance of the fisherman, one of the characters from Visions of Cubanosophy. The performance ended with the fisherman perched on a rock reading Severo Sarduy’s poem “Black Hole IV”. Just after the performance, the police, together with the authorities of the Port Captainship and State Security Agents, barged in and ordered that the exhibition be evacuated, despite the fact that the organizers claimed to have all the licenses necessary for the urban intervention. None of the works shown were of an openly political or counter-revolutionary character. Perhaps the granters of the permits realized too late that the intervention of public space had a specific territorial and temporal reference: it was on another fifth of August, in 1994, throughout the length of the Avenida del Puerto, that the popular Havana protest known as the Maleconazo took place.[5] El Ciervo Encantado’s performance in “Territorial References” brought to light once again the important role played by alternative artistic proposals that resignify life in the city, “questioning who, what, where, and in what circumstances culture is produced… to polemicize, to construct another reading of the quotidian without an official spokesperson. They teach us, then, to see urban space as a democratic space of contemporary life” (Antonacci Ramos 2009, 1579-80).[6] In this case, the invasion of the uninvited group into the space of the exhibit, which was itself invading urban space, doubly threatened “officialdom.” “Territorial References” anticipated by four years the XI Havana Biennial, in which the opening of a “new” space for the exhibit “Detrás del muro” (“Behind the wall”), precisely in the Malecón and the Avenida del Puerto from the Castillo de la Punta to Maceo Park, was announced as a newsworthy event.[7]

In 2008, a group of independent artists, including several visual art students from ISA, decided to put together an exhibition entitled “Referencias territoriales” (“Territorial References”) in an abandoned pier in the Avenida del Puerto. These young artists, conscious that the National Council on Fine Arts wields the power to decide where exhibits are held, had opted to locate themselves “on the margins of the conventional legitimizing circuits of ‘Cuban art’ and ‘national culture’” (Casanueva y González). The participating artists shared a conception of art as a representation of real situations based on their own personal experiences. It was therefore not a coincidence that the coordinator invited El Ciervo Encantado to participate in the exhibit, although the invitation was later withdrawn for unknown reasons. Nonetheless, in spite of the withdrawn invitation, the group “invaded” the exhibit the night of the opening with the performance of the fisherman, one of the characters from Visions of Cubanosophy. The performance ended with the fisherman perched on a rock reading Severo Sarduy’s poem “Black Hole IV”. Just after the performance, the police, together with the authorities of the Port Captainship and State Security Agents, barged in and ordered that the exhibition be evacuated, despite the fact that the organizers claimed to have all the licenses necessary for the urban intervention. None of the works shown were of an openly political or counter-revolutionary character. Perhaps the granters of the permits realized too late that the intervention of public space had a specific territorial and temporal reference: it was on another fifth of August, in 1994, throughout the length of the Avenida del Puerto, that the popular Havana protest known as the Maleconazo took place.[5] El Ciervo Encantado’s performance in “Territorial References” brought to light once again the important role played by alternative artistic proposals that resignify life in the city, “questioning who, what, where, and in what circumstances culture is produced… to polemicize, to construct another reading of the quotidian without an official spokesperson. They teach us, then, to see urban space as a democratic space of contemporary life” (Antonacci Ramos 2009, 1579-80).[6] In this case, the invasion of the uninvited group into the space of the exhibit, which was itself invading urban space, doubly threatened “officialdom.” “Territorial References” anticipated by four years the XI Havana Biennial, in which the opening of a “new” space for the exhibit “Detrás del muro” (“Behind the wall”), precisely in the Malecón and the Avenida del Puerto from the Castillo de la Punta to Maceo Park, was announced as a newsworthy event.[7]

“Black Hole in Territorial References”

El Ciervo Encantado (Rapid Response via email)

9 August, 2008

Four days after “Territorial References,” El Ciervo Encantado sent a “Rapid Response” via email alluding to the cancellation of the event. Titled “Hueco negro en Referencias Territoriales” (“Black Hole in Territorial References”), the email juxtaposed phrases from the Sarduy text read in the performance with pictures of the event.

Traditionally, the distortion of space around a massive body is compared with that of a horizontal, rubber membrane beneath the weight of a ball.

When a gravitational disruption is produced, we witness the birth of a true hole in space-time, a hole that totally devours the matter of the object.

It is the same geometry of space-time that, in a certain area, is dragged by the disruption.

All matter, all light projected through this area is irreversibly captured and cannot escape.

Therefore, no signal from the disrupted object can reach us.

It is thus explained why these celestial objects that have reached such extreme phases of collapses are called “black holes.”

…black holes.

This virtual action, similar to the I-Meil Gallery that Lazaro Saavedra started during the email war, was above all a subtle artistic reference to the “Quick Response Brigades”—pro-government groups that take to the streets to undermine or physically and verbally attack people labeled as dissidents. The association of Sarduy’s text with the images of the performance that took place amid the works of the exhibit underlined the intention of “Territorial References” (both exhibit and performance): the transformation of an empty and abandoned urban space into a gallery that took the ruins—the rubble, trash, and rocks—as raw materials for a work of art that ontologically and epistemologically questioned the meaning of art and the line between art and being. The fisherman/Lorelis Amores, sitting with her book in front of the piece “Cuban Art” or by the altar/installation created from mounds of white sand and containers of products purchased in convertible currency, both formed and did not form a part of that black hole. From the disappeared Lorelis, in whose body the fisherman was reincarnated, and from the ruins transformed into art only to be demolished once again, we did get signals, even if they were electronic. The performance—ephemeral repertory of emptiness—and the annihilation of the work of art that questions itself as such resisted disappearance in “Rapid Response.”

Tempest and Tranquility

Mariela Brito, Lorelis Amores, Eduardo Martínez

Street intervention and performance in the exhibition Tempest and Tranquility by artist Álisar Jalil

30 March, 2009

Galería Galiano, Havana, Cuba

In La tempestad y la calma (Tempest and Tranquility), the fisherman/Lorelis Amores returns together with two characters from De donde son los cantantes (From Cuba With a Song),  El Cristo-Sarduy/Eduardo Martín and Auxilio/Mariela Brito. The three characters used bicycle taxis to ride down the very central Galiano Street to reach the Galiano Gallery and participate in the opening of visual artist Áisar Jalil’s exhibition “Tempest and Tranquility” in the context of the Tenth Havana Biennial. Jalil’s paintings present zoomorphic figures that allude to the “animalization” of individuals and the multiple metamorphoses of being in the Darwinian struggle for survival. The impact of the urban environment on the individual and the consequent moral exhaustion are the pretexts for Tempest and Tranquility. El Ciervo Encantado’s performance, which shared the visual artist’s concerns, seemed to invert dizzyingly Jalil’s proposal. The first words pronounced by El Cristo-Sarduy/Eduardo were: “The street is destroyed.” Making references to a bygone era in Cuba, he saw in the post-Soviet bicycle taxi the coach car of the past. As she arrived in the gallery, Auxilio/Mariela did not understand why there were so many people. “I think we will make a good impression,” she said to Sarduy before entering. “We will leave with an invitation to MOMA.” Once inside the gallery, the confused Auxilio asked: “What is this? Where have you brought me?” And Sarduy, responding eloquently, made it clear that “this is an exhibition of modern art.” Like Sarduy’s cobra that bites its own tail, the performance took the individual back to the street in order to explore the effect on the urban environment and on the citizens of those performers/beings who embodied and were the result of an investigation about the effects of urban and cultural degradation in the individual. The questions about the meaning of art were combined with comments/gossip about daily life, culminating in the key moment of dizzying inversions when Auxilio saw “the shameless one” or the “bald one” (death), a character from De donde son los cantantes (From Cuba With a Song), in one of Jalil’s paintings

El Cristo-Sarduy/Eduardo Martín and Auxilio/Mariela Brito. The three characters used bicycle taxis to ride down the very central Galiano Street to reach the Galiano Gallery and participate in the opening of visual artist Áisar Jalil’s exhibition “Tempest and Tranquility” in the context of the Tenth Havana Biennial. Jalil’s paintings present zoomorphic figures that allude to the “animalization” of individuals and the multiple metamorphoses of being in the Darwinian struggle for survival. The impact of the urban environment on the individual and the consequent moral exhaustion are the pretexts for Tempest and Tranquility. El Ciervo Encantado’s performance, which shared the visual artist’s concerns, seemed to invert dizzyingly Jalil’s proposal. The first words pronounced by El Cristo-Sarduy/Eduardo were: “The street is destroyed.” Making references to a bygone era in Cuba, he saw in the post-Soviet bicycle taxi the coach car of the past. As she arrived in the gallery, Auxilio/Mariela did not understand why there were so many people. “I think we will make a good impression,” she said to Sarduy before entering. “We will leave with an invitation to MOMA.” Once inside the gallery, the confused Auxilio asked: “What is this? Where have you brought me?” And Sarduy, responding eloquently, made it clear that “this is an exhibition of modern art.” Like Sarduy’s cobra that bites its own tail, the performance took the individual back to the street in order to explore the effect on the urban environment and on the citizens of those performers/beings who embodied and were the result of an investigation about the effects of urban and cultural degradation in the individual. The questions about the meaning of art were combined with comments/gossip about daily life, culminating in the key moment of dizzying inversions when Auxilio saw “the shameless one” or the “bald one” (death), a character from De donde son los cantantes (From Cuba With a Song), in one of Jalil’s paintings .[8] We will see the epitome of the animalization of the individual in El Ciervo Encantado’s last performance, Rapsodia para el mulo (Rhapsody for the Mule). Finally, Tempest and Tranquility once again anticipated works shown in the ninth Biennial, transforming a mode of public transportation—the bicycle taxi—into art to question the line between art and reality. But Ciervo Encantado did so without official intermediaries and without necessarily creating an artistic bicycle taxi such as the vehicle created by Liudmila López Domínguez’s (Lud) and Sandra Pérez to be driven by Jorge Perrugoria, the actor from Strawberry and Chocolate, in the 2012 Biennial (Armas Fonseca 2012).

.[8] We will see the epitome of the animalization of the individual in El Ciervo Encantado’s last performance, Rapsodia para el mulo (Rhapsody for the Mule). Finally, Tempest and Tranquility once again anticipated works shown in the ninth Biennial, transforming a mode of public transportation—the bicycle taxi—into art to question the line between art and reality. But Ciervo Encantado did so without official intermediaries and without necessarily creating an artistic bicycle taxi such as the vehicle created by Liudmila López Domínguez’s (Lud) and Sandra Pérez to be driven by Jorge Perrugoria, the actor from Strawberry and Chocolate, in the 2012 Biennial (Armas Fonseca 2012).

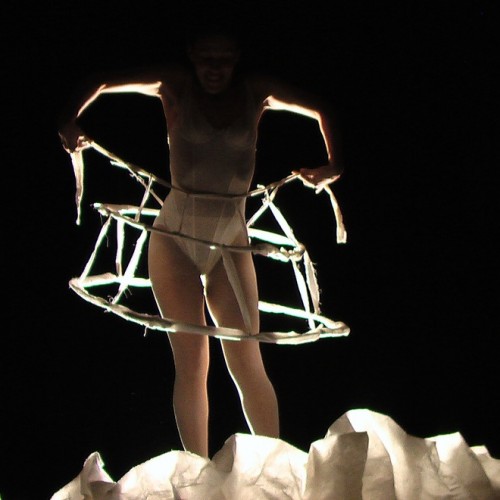

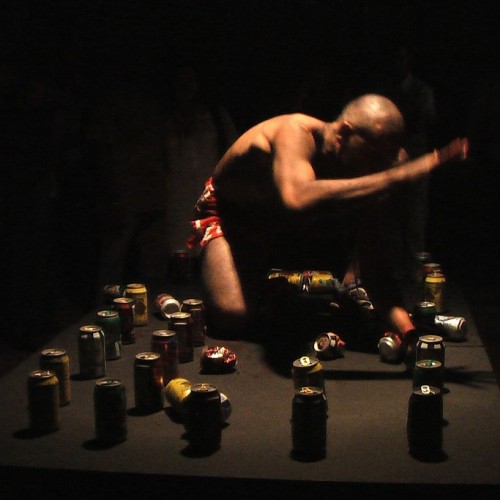

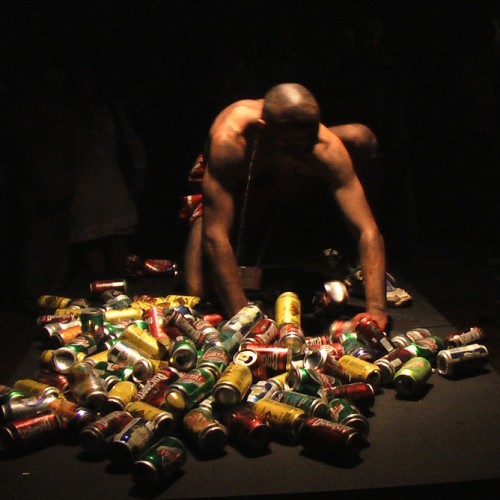

Floating Islands

Mariela Brito

2011

I Will Go to Santiago

Lorelis Amores

2011

Escachalataescachalataescach

Eduardo Martínez

Performance in the collective exhibit Then Cuba.

2011

La Casona Gallery, Havana

Floating Islands

I Will Go to Santiago

Escachalataescachalataescach

These shipwrecked coffers, territorial references, and tempests and calms suggest a relation to another distinctively Caribbean poetics: Marysé Condé’s “poetics of the mangrove” and its reformulation in Alexandra Vásquez’s essay “Learning to Live Miami.” Condé’s 1989 novel Traversée de la Mangrove introduces the mangrove as a living figure that symbolizes Caribbean adaptation and writing/art as a process. The mangrove, as is well known, is an ecosystem that takes its name from the mangle, the main tree that sustains it. The mangrove is both tree and bush, lives in both salt and fresh water, has roots that are also aerial, and feeds from the wastes that flow its way. Vásquez suggests that “no matter what is done to [mangroves], they still grow up and out into mineral-rich, mangled structures that carry the smells and sounds of antiquity and futurity. Mangroves must form some kind of adaptable relationship to whatever comes their way… Mangroves offer an alternative sense of those geographies that blur the acá/allá (here/there)” (2014, 859). This ecosystem erases the line between land and sea, and the labyrinth/mangle of its roots evokes the concept of the rhizome that Edouard Glissant takes from Deleuze and Guattari and transforms into a metaphor for Caribbean relationality. The poetics of the mangrove, as an ecosystem and as El Ciervo Encantado’s performances, does not admit dualisms or fusions. It is a poetics of construction on the basis of residues from that which is disposed and recycled, on the borderline between the civil and the marginal, the public and the private, on the frontier in which these binaries disappear. El Ciervo Encantado’s poetics of the mangrove is relational and rhyzomatic. As Rancière suggests, “In ‘relational’ art, the creation of an indecisive and ephemeral situation requires the displacement of perception, a shift from the status of spectator to that of actor, a reconfiguration of places…. The specificity of art consists in effectuating a new distribution of material and symbolic space. And that is how art bears upon politics” (2005, 6).

[1] The rest of the collaborations can be found in the Cuban Theater Digital Archive.

[2] See Manzor 2012 for a history of this cancellation and Weiss 2011 for an analysis of the period in terms of fine art.

[3] “There was a Sputnik journal, a radio, a Communist youth credential that once belonged to the artist, his first passport, an aluminum jar from a ‘rural school,’ a Misha bear…the work ‘Las iniciales de la Tierra’ of the deceased and controversial Cuban artist Jesús Díaz (the founding director of the journal Encuentro), medals of the Heroes of Labor, a Vinyl of Farah María…a Political Economy Manual (socialist and printed in the Soviet Union, naturally)…a picture frame made with the wooden sticks of popsicles…a chapel of an international brigadier who went to Angola, Silvio’s Tryptich, a bottle of Georgian brandy and another of Bulgarian wine” (“Una instalación ocurrente”).

[4] I thank Ernesto Fundora Castro for this interpretation of the performance as an exorcism, as well as for his valuable comments on this essay.

[5] For an analysis of the event, see Gámez Torres 2014.

[6] Antonacci Ramos is using “democracy” in a different sense than Rancière’s theorization.

[7] The Biennial, from the moment of its founding in 1984, has tried to push beyond galleries and museums and transform the street into a meeting place for art and the audience. Nonetheless, as Juan Delgado Calzadilla, the curator and coordinator of “Detrás del muro,” noted, ‘Even though the Malecón was the object of other actions, they never reached that magnitude….[I conceived] the idea as an homage to the Cubans who, in a dialogue of faith with the sea, dream that another world is possible’” (“Inauguran”).

[8] As Jalil himself has said, “Some time before the exhibit I went to see a show of the theatrical group El Ciervo Encantado. I then discovered that the aesthetic sense of this collective directed by Nelda Castillo is very strong. Visual elements hold a heavy weight. There were many points of coincidence between my proposal and theirs, in which characters based on my iconography appear” (Estrada Betancourt 2011).